249. The research just completed has called our attention—along with a number of incidental inductions—to the following facts:

1. The existence and importance of non-logical conduct. That runs counter to many sociological theories that either scorn or ignore non-logical actions, or else, in an effort to reduce all conduct to logic, attach little importance to them. The course we follow in studying the behaviour of human beings as bearing on the social equilibrium differs according as we lay the greater stress on logical or non-logical conduct. We had better look into that matter more deeply, therefore.

2. Non-logical actions are generally considered from the logical standpoint both by those who perform them and by those who discuss them and generalize about them. Hence our need to do a thing of supreme importance for our purposes here—to tear off the masks non-logical conduct is made to wear and lay bare the things they hide from view. That too runs counter to many theories which halt at logical exteriors, representing them not as masks but as the substantial element in conduct itself. We have to scrutinize those theories closely: for if we were to find them true—in accord with experience, that is—we would have to follow an altogether different course from the one we would follow were we to discover that the substantial element in the conduct lies in the things that underlie the logical exteriors (§ 146).

3. The experimental truth of a theory and its social utility are different things. A theory that is experimentally true may be now advantageous, now detrimental, to society; and the same applies to a theory that is experimentally false. Many many people deny that. We must therefore not rest satisfied with the rapid survey we have made so far, much less with the bald declaration in § 72. We must see whether observation of the facts confirms or belies our induction (§§ 72-73).

4. As regards logical and non-logical conduct there are differences between individual human beings, or, taking things in the mass, between social classes, and differences also in the degrees of utility that theories experimentally true or experimentally false have for individuals or classes. And the same applies to the sentiments that are expressed through non-logical conduct. Many people deny such differences. To not a few the mere suggestion that they exist seems scandalous. It will therefore be necessary to continue our examination of that subject, on which we have barely touched, and clearly establish just what the facts have to say.

250. Meantime, our first survey has already given us an idea, however superficial, of the answers that have to be given to the inquiries suggested in §§ 13-14 as to the motives underlying theories, as to their bearing on experimental realities, and as to individual and group utilities—and we see that some at least of the distinctions that are drawn in those paragraphs are not merely hypothetical, but have points of correspondence with reality.

251. In the following pages we shall devote ourselves chiefly to running down non-logical actions in the theories or descriptions of social facts that have been put forward by this or that writer; and that will give us an approximate notion of the way non-logical conduct is masked by logic.

252. If non-logical actions are really as important as our induction so far would lead us to suppose, it would be strange indeed that the many men of talent who have applied themselves to the study of human societies should not have noticed them in any way. Distracted by preconceptions or led astray by erroneous theories, they may, "as they that have spent eyes," have caught imperfect glimpses of them; but it is hard to believe that they can have seen nothing where we find so much that is of such great significance. Let us therefore see just how the matter stands.

253. But for that purpose we have to take an even more general view of things: we have to see to what extent reality is disfigured in the theories and descriptions of it that one finds in the literature of thought. We have an image in a curved mirror; our problem is to discover the form of the object so altered by refraction.

Suppose we ignore, for the moment, the simplest case of writers who understand that the conduct of human beings depends, to some extent at least, on the environment in which they live, on climate, race, occupation, "temperament." It is obvious that the behaviour resulting from such causes is not the product of pure ratiocination, that it is non-logical behaviour. To be sure, that fact is often overlooked by the very writers who have stressed it, and they therefore seem to be contradicting themselves. But the inconsistency is now and again more apparent than real; for when a writer admits such causes he is usually dealing with what is—and that is one thing. When he insists on having all conduct logical, he is usually describing what, in his opinion, ought to be—and that is quite another thing. From the scientific laboratory he steps over into the pulpit.

254. Let us begin with cases not quite so simple but where it is still easy to perceive the experimental truth underneath imperfect and partly erroneous descriptions of it.

Here, for instance, is The Ancient City of Fustel de Coulanges. In it we read, p. 73 (Small, p. 89): "From all these beliefs, all these customs, all these laws, it clearly results that from the religion of the hearth human beings learned to appropriate the soil and on it based their title to it." But, really, is it not surprising that domestic religion should have preceded ownership of land? And Fustel gives ho proof whatever of such a thing! The opposite may very well have been the case—or religion and ownership of land may have developed side by side. It is evident that Fustel has the preconceived notion that possession has to have a "cause." On that assumption, he seeks the cause and finds it in religion; and so the act of possession becomes a logical action derived from religion, which in its turn can now be logically derived from some other cause. By a singular coincidence it happens that in this instance Fustel himself supplies the necessary rectification. A little earlier, p. 63 (Small, p. 78), he writes: "There are three things which, from the most ancient times, one finds founded and solidly established in these Greek and Italian communities: domestic religion, the family, the right of property— three things which were obviously related in the beginning and which seem to have been inseparable."

How did Fustel fail to see that his two passages were contradictory? If three things A, B, C are "inseparable," one of them, for instance A, cannot have produced another, for instance B: for if A produced B, that would mean that, at the time, A was separate from B. We are therefore compelled to make a choice between the two propositions. If we keep the first, we have to discard the second, and vice versa. As a matter of fact, we have to adopt the second, discarding the proposition that places religion and property in a relationship of cause and effect, and keeping the one that puts them in a relationship of interdependence (§§ 138, 267). The very facts noted by Fustel himself force that choice upon us. He writes, p. 64 (Small, p. 79): "And the family, which by duty and religion remains grouped around its altar, becomes fixed to the soil like the altar itself." But the criticism occurs to one of its own accord: "Yes, provided that be possible!" For if we assume a social state in which the family cannot settle on the soil, it is the religion that has to be modified. What obviously has happened is a series of actions and reactions, and we are in no position to say just how things stood in the beginning. The fact that certain people came to live in separate families fixed to the soil had as one of its manifestations a certain kind of religion; and that religion, in its turn, contributed to keeping the families separate and fixed to the soil (§ 1021).

255. In this we have an example of a very common error, which lies in substituting relationships of cause and effect for relationships of interdependence (§ 138); and that error gives rise to still another: the error of placing the alleged effect, erroneously regarded as the logical product of the alleged cause, in the class of logical actions.

256. When Polybius stresses religion as one of the causes of the power of Rome (§ 313), we will accept the remark as very suggestive; but we will reject the logical explanation that he gives of the fact (§ 3131)

In Sumner Maine's Ancient haw, p. 122, we find another example like Fustel's. Maine observes that ancient societies were made up of families. That is a question of fact which we choose not to go into— researches into origins are largely hypothetical anyway. Let us accept Maine's data for what they are worth—just as hypotheses. From the fact he draws the conclusion that ancient law was "adjusted to a system of small independent corporations." That too is good: institutions adjust themselves to states of fact! But then suddenly we find the notion of logical conduct creeping stealthily in, p. 177: "Men are regarded and treated, not as individuals, but always as members of a particular group." It would be more exact to say that men are that in reality, and law, accordingly, develops as if men were regarded and treated as members of a particular group.

A little earlier, Maine's intromission of logical conduct is more obtrusive. Following his remark that ancient societies were made up of small independent corporations, he adds, p. 122: "Corporations never die, and accordingly primitive law considers the entities with which it deals, i.e., patriarchal or family groups, as perpetual and inextinguishable." From that Maine derives as a consequence the institution of transmission, upon decease, of the universitas iuris, which we find in Roman law. Such a logical sequence may easily be compatible with a posterior logical analysis of antecedent non-logical actions, but it does not picture the facts accurately. To come nearer to them we have to invert some of the terms in Maine's previous remarks. The succession of the universitas iuris does not derive from the concept of a continuous corporation: the latter concept derives from the fact of succession. A family, or some other ethnic group, occupies a piece of land, comes to own flocks, and so on. The fact of perpetuity of occupation, of possession, is in all probability antecedent to any abstract concept, to any concept of a law of inheritance. That is observable even in animals. The great felines occupy certain hunting-grounds and these remain properties of the various families, unless human beings chance to interfere.1 The ant-hill is perpetual, yet one may doubt whether ants have any concept of the corporation or of inheritance. In human beings, the fact gave rise to the concept. Then man, being a logical animal, had to discover the "why" of the fact; and among the many explanations he imagined, he may well have hit upon the one suggested by Sumner Maine.

Maine is one of the writers who have best shown the difference between customary law (law as fact) and positive law (law as theory); yet he forgets that distinction time and again, so persuasive is the concept that posits logical conduct everywhere. Customary law is made up of a complex of non-logical actions that regularly recur. Positive law comprises two elements: first, a logical—or pseudo-logical or even imaginary—analysis of the non-logical actions in question; second, implications of the principles resulting from that analysis. Customary law is not merely primitive: it goes hand in hand with positive law, creeps unobtrusively into jurisprudence, and modifies it. Then the day comes when the theory of such modifications is formulated—the caterpillar becomes a butterfly—and positive law opens a new chapter.

257. Of the assassination of Caesar, Duruy writes:1 "Ever since the foundation of the Republic the Roman aristocracy had adroitly fostered in the people a horror for the name of king." In that the logical varnish for conduct that is non-logical is easily recognizable. Then he goes on: "If the monarchical solution answered the needs of the times, it was almost inevitable that the first monarch should pay for his throne with his life, as our Henry IV paid for his." In such "needs of the times" we recognize at once one of those amiable fictions which historians try to palm off as something concrete. As for the law that first monarchs in dynasties have to die by assassination, history gives no experimental proof of any such fact. We have to see in it a mere reminiscence of the classical fatum, and pack it off to keep company with many similar products of the scholarly fancy.

258. Shall we banish from history the prodigies that Suetonius never forgets to enumerate in connexion with the births or deaths of the Roman Emperors, without trying to interpret them—for we shall see how mistaken such an effort on our part would be (§ 672)—and shall we keep only such of his facts as are, or at least seem to be, historical? Shall we do the same with all similar historical sources—for instance, with histories of the Crusades?1

In doing that we should be on dangerous ground, for if we made it an absolute rule to divide all our narrative sources into two elements, one miraculous, incredible, which we reject, and another natural, plausible, which we retain, we should certainly fall into very serious errors (§ 674). The part that is accepted has to have extrinsic probabilities of truth, whether through the demonstrable credibility of the author or through accord with other evidence.

259. From a legend we can learn nothing that is strictly historical; but we can learn something, and often a great deal, about the psychic state of the people who invented or believed it; and on knowledge of such psychci states our research is based. We shall therefore often cite facts without trying to ascertain whether they are historical or legendary; because for the use we are going to make of them they are just as serviceable in the one case as in the other—sometimes, indeed, they are better legendary than historical.

260. Logical interpretations of non-logical conduct become in their turn causes of logical conduct and sometimes even of non-logical conduct; and they have to be reckoned with in determining the social equilibrium. From that standpoint, the interpretations of plain people are generally of greater importance than the interpretations of scholars. As regards the social equilibrium, it is of far greater moment to know what the plain man understands by "virtue" than to know what philosophers think about it.

261. Rare the writer who fails to take any account of non-logical conduct whatever; but generally the interest is in certain natural inclinations of temperament, which, willynilly, the writer has to credit to human beings. But the eclipse of logic is of short duration— driven off at one point, it reappears at some other. The rôle of temperament is reduced to lowest terms, and it is assumed that people draw logical inferences from it and act in accordance with them.

262. So much for the general situation. But in the particular, theorists have another very powerful motive for preferring to think of non-logical conduct as logical. If we assume that certain conduct is logical, it is much easier to formulate a theory about it than it is when we take it as non-logical. We all have handy in our minds the tool for producing logical inferences, and nothing else is needed. Whereas in order to organize a theory of non-logical conduct we have to consider hosts and hosts of facts, ever extending the scope of our researches in space and in time, and ever standing on our guard lest we be led into error by imperfect documents. In short, for the person who would frame such a theory, it is a long and difficult task to find outside himself materials that his mind supplied directly with the aid of mere logic when he was dealing with logical conduct.

263. If the science of political economy has advanced much farther than sociology, that is chiefly because it deals with logical conduct.1 It would have been a soundly constituted science from the start had it not encountered a grave obstacle in the interdependence of the phenomena it examines, and at a time when the scholars who were devoting themselves to it were unable to utilize the one method so far discovered for dealing with interdependencies. The obstacle was surmounted, in part at least, when mathematics came to be applied to economic phenomena, whereby the new science of mathematical economics was built up, a science well able to hold its own with the other natural sciences.2

264. Other considerations tend to keep thinkers from the field of non-logical conduct and carry them over into the field of the logical. Most scholars are not satisfied with discovering what is. They are anxious to know, and even more anxious to explain to others, what ought to be. In that sort of research, logic reigns supreme; and so the moment they catch sight of conduct that is non-logical, instead of going ahead along that road they turn aside, often seem to forget its existence, at any rate generally ignore it, and beat the well-worn path that leads to logical conduct.

265. Some writers likewise rid themselves of non-logical actions by regarding them—often without saying as much explicitly—as scandalous things, or at least as irrelevant things, which should have no place in a well-ordered society. They think of them as "superstitions" that ought to be extirpated by the exercise of intelligence. Nobody, in practice, acts on the assumption that the physical and the moral constitution of an individual do not have at least some small share in determining his behaviour. But when it comes to framing a theory, it is held that the human being ought to act rationally, and writers deliberately close their minds to things that the experience of every day holds up before their eyes.

266. The imperfection of ordinary language from the scientific standpoint also contributes to the wide-spread resort to logical interpretations of non-logical conduct.

267. It plays no small part in the common misapprehension whereby two phenomena are placed in a relationship of cause and effect for the simple reason that they are found in company. We have already alluded to that error (§ 255); but we must now advance a little farther in our study of it, for it is of no mean importance to sociology.

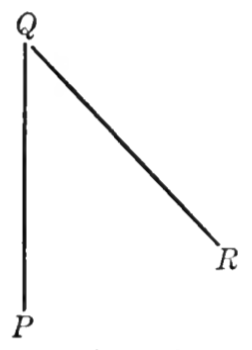

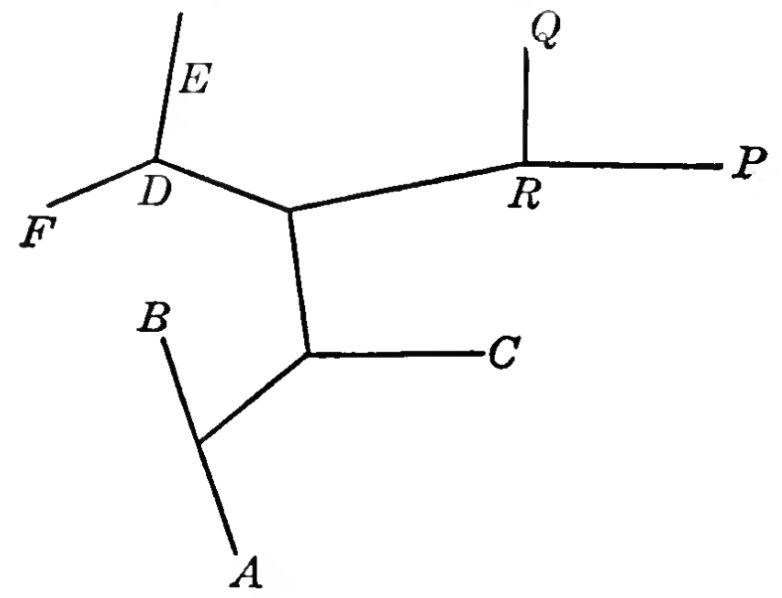

Let C, as in Figure 3, § 166, stand for a belief; D, for certain behaviour. Instead of saying simply, "Some people do D and believe C," ordinary speech goes farther and says, "Some people do D because they believe C." Taken strictly, that proposition is often false. Less often false is the proposition, "Some people believe C because they do D." But there are still many occasions when all that we can say is, "Some men do D and believe C."

In the proposition, "Some people do D because they believe C," the logical strictness of the term "because" can be so attenuated that no relationship of cause and effect is set up between C and D. We can then say, "We may assume that certain people do D because they have a belief C which expresses sentiments that impel them to do D"; that is because (going back to Figure 3), they have a psychic state A that is expressed by C. In such a form the proposition closely approximates the truth, as we saw in § 166.

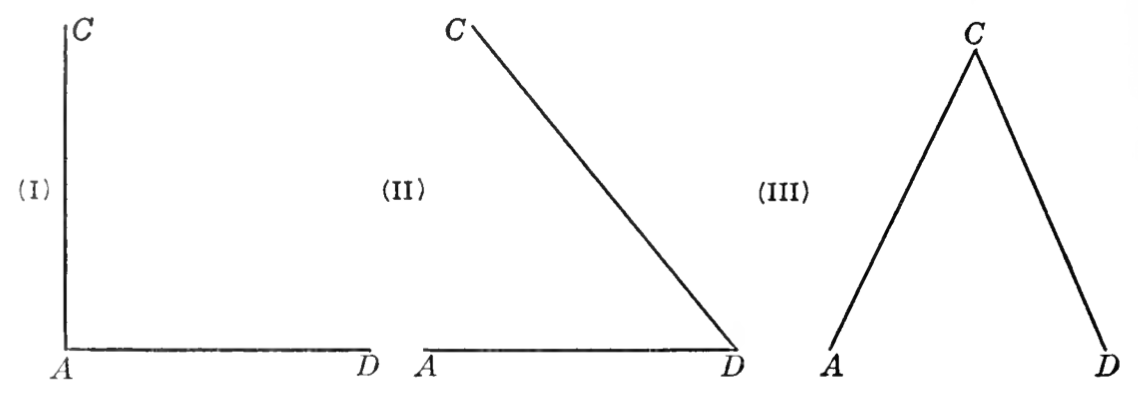

268. Figure 3 can be broken up into three others (Figure 7).

I. The psychic state A produces the belief C and the conduct D, there being no direct relation between C and D. That is the situation in the proposition, "People do D and believe C."

II. The psychic state A gives rise to the conduct D, and they both produce the belief C. That is the situation in the second proposition, "People believe C because they do D."

III. The psychic state A gives rise to the belief C, which produces the behaviour D. That is the situation in the proposition, "People do D because they believe C."

269. Although case III is not the only case, nor even the most frequent case, people are inclined to regard it as general and to merge with it cases I and II to which they preferably attribute little or no importance. Ordinary language, with its lack of exactness, encourages the error, because a person may state case III explicitly and be unconsciously thinking meantime of cases I and II. It often happens, besides, that we get mixtures of the three cases in varying proportions.

270. Aristotle opens his Politics, I, 1, 1 (Rackham, p. 3), with the statement: "Seeing that every city is a society (Rackham, "partnership") and that every society (partnership) is constituted to the end of some good (for all men work to achieve what to them seems good) it is manifest that all societies (partnerships) seek some good." Here we stand altogether in the domain of logic: with a deliberate purpose—the purpose of achieving a certain good—human beings have constituted a society that is called a city. It would seem as though Aristotle were on the point of going off into the absurdities of the "social contract"! But not so. He at once changes tack, and the principle he has stated he will use to determine what a city ought to be rather than what it actually is.

271. The moment Aristotle has announced his principle—an association for purposes of mutual advantage—he tosses it aside and gives an altogether different account of the origin of society. First he notes the necessity of a union between the sexes, and soundly remarks that "that does not take place of deliberate choice"1; wherewith, evidently, we enter the domain of non-logical conduct. He continues: "Nature has created certain individuals to command and others to obey." Among the Greeks Nature has so distinguished women and slaves. Not so among the Barbarians, for among the Barbarians, Nature has not appointed any individuals to command. We are still, therefore, in the domain of non-logical conduct; nor do we leave it when Aristotle explains that the two associations of master and slave, husband and wife, are the foundations of the family, that the village is constituted by several families, and that several villages form a state; nor when, finally, he concludes with the explicit declaration that "Every city, therefore, like the original associations, comes of Nature."2 One could not allude to non-logical actions in clearer terms.

272. But, alas, if the city comes of Nature, it does not come of the deliberate will of citizens who get together for the purpose of achieving a certain advantage! There is an inconsistency between the principle first posited and the conclusion reached.1 Just how Aristotle fell into it we cannot know, but to accomplish that feat for oneself, one may proceed in the following fashion: First centre exclusively on the idea of "city," or "state." It will then be easy to connect city, or state, with the idea of "association," and then to connect association with the idea of deliberate association. So we get the first principle. But now think, in the second place, of the many many facts observable in a city or a state—the family, masters and slaves, and so on. Deliberate purpose will not fit in with those things very well. They suggest rather the notion of something that develops naturally. And so we get Aristotle's second description.

273. He gets rid of the contradiction by metaphysics, which never withholds its aid in these desperate cases. Recognizing non-logical conduct, he says, I, 1, 12 (Rackham, pp. 11-13): "It is therefore manifest that the city is a product of Nature and is superior (prior) to man (to the individual). From Nature accordingly comes the tendency (an impulse) in all men toward such association. Therefore the man who first founded one was the cause of a very great good." So then, there is the inclination imparted by Nature; but it is further necessary that a man found the city. So a logical action is grafted upon the non-logical action (§ 306, I-β); and there is no help for that, for, says Aristotle, Nature does nothing in vain.1 Our best thanks, therefore, to that estimable demoiselle for so neatly rescuing a philosopher from a predicament!

274. In distinguishing the Greeks from the Barbarians in his celebrated theory of natural slavery, Aristotle avails himself of the concept of non-logical conduct. It is obvious, among other things, that logic being the same for Greeks and Barbarians, if all actions were logical there could not be any difference between Greeks and Barbarians. But that is not all. Good observer that he is, Aristotle notices differences among Greek citizens. Speaking of the forms of democracy he says, VI, 2, 1 (Rackham, pp. 497-98): "Excellent is an agricultural people; consequently one can institute a democracy where a people lives by farming and sheep-raising." And he repeats, VI, 2, 7 (Rackham, p. 503): "Next after farmers, the best people are shepherds, or people who live by owning cattle. . . . The other rabbles on which other sorts of democracy are based are greatly inferior." Here then we get clearly distinguished classes of citizens and almost a rudimentary economic determinism. But there is no reason for our stopping where Aristotle stops; and if we do go on we see that in general the conduct of human beings depends on their temperaments and occupations.

Cicero credits the ancestors of the Romans of his time with knowing that "the characters of human beings result not so much from race and family as from those things which are contributed by the nature of their localities for the ordinary conduct of life, and from which we draw our livelihood and subsistence. The Carthaginians were liars and cheats not by race but from the nature of their country, which with its port and its contacts with all sorts of merchants and foreigners speaking different languages inclined them through love of profits to love of trickery. The mountaineers of Liguria are harsh and uncouth. . . . The Capuans have ever been a supercilious people, because of the fertility of their soil, the wealth of their harvests, the salubriousness, the disposition, and the beauty of their city."1

275. In his Rhetoric, II, 12-14 (Freese, pp. 247-57), Aristotle makes an analysis, which came to be celebrated, of the traits of man according to age—in adolescence, in maturity, and in senility. He pushes his analysis further still, II, 12, 17 (Freese, pp. 257-63), and examines the effects on character of noble birth, wealth, and power—a splendidly conducted study. But all that evidently carries him into the domain of non-logical conduct.1

276. Aristotle even has the concept of evolution. In the Politics, II, 5, 12 (Rackham, pp. 129-31), he remarks that the ancestors of the Greeks probably resembled the vulgar and ignorant among his contemporaries.

277. Had Aristotle held to the course he in part so admirably followed, we would have had a scientific sociology in his early day. Why did he not do so? There may have been many reasons; but chief among them, probably, was that eagerness for premature practical applications which is ever obstructing the progress of science, along with a mania for preaching to people as to what they ought to do—an exceedingly bootless occupation—instead of finding out what they actually do. His History of Animals avoids those causes of error, and that perhaps is why it is far superior to the Politics from the scientific point of view.

278. It might seem strange to find traces of the concept of non-logical conduct in a dreamer like Plato; yet there they are! The notion transpires in the reasons Plato gives for establishing his colony far from the sea. To be near the sea begins by "being sweet" but ends by "being bitter" for a city: "for filling with commerce and traffic it develops capricious, untrustworthy instincts, and a breed of tricksters."1 Non-logical conduct has its place also in the well-known apologue of Plato on the races of mankind. The god who fashioned men mixed gold into the composition of those fit to govern, silver in guardians of the state (the warriors), iron in tillers of the soil and labourers. Plato also has a vague notion of what we are to call class-circulation, or circulation of élites (§§ 2026 f.). He knows that individuals of the silver race may chance to be born in the race of gold, or vice versa, and so for the other races.2

279. That being the case, if one would remain within the domain of science, one must go on and investigate the probable characteristics and the probable evolution of a society made up of different races of human beings, which are not reproduced from generation to generation with exactly the same characteristics and which are able to mix. That would be working towards a science of societies. But Plato has a very different purpose. He is little concerned with what is. He strains all his intellectual capacities to discover what ought to be. And thereupon non-logical conduct vanishes, and Plato's fancy goes sporting about among logical actions, which he invents in great numbers; and we find him at no great cost to himself appointing magistrates to put individuals who are born in a class but differ in traits from their parents in their proper places, and proclaiming laws to preserve or alter morals—in short, deserting the modest province of science to rise to the sublime heights of creation.

280. The controversies on the question "Can virtue be taught?" also betray some distant conception of non-logical conduct. According to the documents in our possession, it would seem that Socrates regarded virtue as a science and left little room for non-logical actions.1 Plato and Aristotle abandon that extreme position. They hold that a certain natural inclination is necessary to "virtue." But that inclination once premised, back they go to the domain of logic, which is now called in to state the logical implications of temperament, and these in their turn determine human conduct. Those old controversies have points of resemblance with the disputes which took place long afterwards on "efficacious," and "non-efficacious," grace.

281. The procedure of Plato and Aristotle in the controversies on the teaching of "virtue" is a general one. Non-logical actions are credited with a rôle that it would be absurd not to give them, but then that rôle is at once withdrawn, and people go back to the logical implications of inclinations; and by dividing those inclinations, which in fact cannot be ignored, into "good" ones and "bad" ones, a way is found to keep inclinations that are in accord with the logical system one prefers and to eliminate all others.

282. St. Thomas tries to steer a deft course between the necessity of recognizing certain non-logical inclinations and a great desire to give full sway to reason, between the determinism of non-logical conduct and the doctrine of free will that is implicit in logical conduct. He says that "virtue is a good quality or disposition (habitus) of the soul, whereby one lives uprightly, which no one uses wrongly, and which God produces within us apart from any action by ourselves."1 Taken as a "disposition of the soul" virtue is classed with non-logical actions; and so it is when we say that God produces it in us apart from anything we do of ourselves. But by that divine interposition any uncertainty as to the character of non-logical conduct is removed, for it becomes logical according to the mind of God and therefore logical for the theologians who are so fortunate as to know the divine mind. Others use Nature for the same purpose and with the same results. People act according to certain inclinations. That reduces the rôle of the non-logical to a minimum, actions being regarded as logical consequences of the inclinations. Then even that very modest remnant is made to vanish as by sleight-of-hand; for inclinations are conceived as imparted by some entity (God, Nature, or something else) that acts logically (§ 306, I-β); so that even though the acting subject may on occasion believe that his actions are non-logical, those who know the mind, or the logical procedure, of the entity in question—and all philosophers, sociologists, and the like, have that privilege—know that all conduct is logical.

283. The controversy between Herbert Spencer and Auguste Comte brings out a number of interesting aspects of non-logical conduct.

284. In his Lectures on Positive Philosophy (Cours de philosophie positive) Comte seems to be decidedly inclined to ascribe the predominance to logical conduct. He sees in positive philosophy, Vol. I, pp. 48-49, "the one solid basis for that social reorganization which is to terminate the critical state in which civilized nations have been living for so long a time." So then it is the business of theory to reorganize the world! How is that to come about? "Not to readers of these lectures should I ever think it necessary to prove that ideas govern and upset the world, or, in other terms, that the whole social mechanism rests, at bottom, on opinions. They are acutely aware that the great political and moral crisis in present-day society is due, in the last analysis, to our intellectual anarchy. Our most serious distress is caused by the profound differences of opinion that at present exist among all minds as to all those fundamental maxims the stability of which is the prime requisite for a real social order. So long as individual minds fail to give unanimous assent to a certain number of general ideas capable of constituting a common social doctrine, we cannot blind ourselves to the fact that the nations will necessarily remain in an essentially revolutionary atmosphere. . . . It is just as certain that if this gathering of minds to one communion of principles can once be attained, the appropriate institutions will necessarily take shape from it."

285. After quoting Comte's dictum that ideas govern and upset the world, Herbert Spencer advances a theory that non-logical actions alone influence society. "Ideas do not govern and overthrow the world: the world is governed or overthrown by feelings, to which ideas serve only as guides. The social mechanism does not rest finally upon opinions; but almost wholly upon character. Not intellectual anarchy, but moral antagonism, is the cause of political crises. All social phenomena are produced by the totality of human emotions and beliefs. . . . Practically, the popular character, and the social state, determine what ideas shall be current; instead of the current ideas determining the social state and the character. The modification of men's moral natures caused by the continuous discipline of social life, which adapts them more and more to social relations, is therefore the chief proximate cause of social progress."1

286. Then a curious thing happens: Comte and Spencer reverse positions reciprocally! In his System of Positive Polity, Vol. IV, p. 5, Comte decides to allow sentiment to prevail, and expresses himself very clearly on the point: "Though I have always proclaimed the universal preponderance of sentiment, I have had, so far, to devote my attention primarily to intelligence and activity, which prevail in sociology. But the very real ascendancy they have acquired having now brought on the period of their real systematization, the final purpose of this volume must now be to bring about a definite predominance of sentiment, which is the essential domain of morality."

Comte is straining the truth a little when he says that he has "always proclaimed the universal preponderance of sentiment." No trace of any such preponderance is to be detected in his Cours. Ideas stand in the forefront there. But Comte has changed. He began by considering existing theories, which he wished to replace with others of his own make; and in that battle of ideas, his own naturally won the palm, and from them new life was to come to the world. But time rolls on. Comte becomes a prophet. The battle of ideas is over. He imagines he has won a complete victory. So now he begins proclaiming dogma, pronouncing ex cathedra, and it is only natural that nothing but sentiments should now be left on the field—his own sentiments, of course.1

287. Comte, moreover, began by hoping to make converts of people; and naturally the instrument for doing that was, at the time, ideas. But he ended by having no hope save in a religion imposed by force, imposed if need be by Czar Nicholas, by the Sultan, or at the very least by a Louis Napoleon (who would in fact have done better to rest content with being just a dictator in the service of Positivism).1 In this scheme sentiment is the big thing beyond shadow of doubt, and one can no longer say that "ideas govern or upset the world." It would be absurd to suppose that Comte turned to the Czar, to Reshid Pasha, or to Louis Napoleon, to induce them merely to preach ideas to their peoples. One might only object that the ideas of Comte would be determining the religion which would later be imposed upon mankind; and in that case ideas would be "upsetting the world," if the Czar, the Sultan, Louis Napoleon, or some other well-intentioned despot saw fit to take charge of enforcing Comte's positivism upon mankind. But that is far from being the meaning one gathers from the statements in the Cours.

288. Comte recognizes, in fact he greatly exaggerates, the social influence of public worship and its efficacy in education—all of which is just a particular case of the efficacy of non-logical impulses. If Comte could have rested satisfied with being just a scientist, he might have written an excellent book on the value of religions and taught us many things. But he wanted to be the prophet of a new religion. Instead of studying the effects of historical or existing forms of worship, he wanted to create a new one—an entirely different matter. So he gives just another illustration of the harm done to science by the mania for practical applications.

289. Spencer, on the other hand, after admitting, even too sweepingly, the influence of non-logical actions, eliminates them altogether by the general procedure described in § 261. Says he: "Our postulate must be that primitive ideas are natural, and, under the conditions in which they occur, rational."1 Driven out by the door, logic here climbs back through the window. "In early life we have been taught that human nature is everywhere the same. . . . This error we must replace by the truth that the laws of thought are everywhere the same; and that, given the data as known to him, the primitive man's inference is the reasonable inference" (§§ 701, 711).

290. In assuming any such thing, Spencer puts himself in the wrong in his controversy with Comte. If human beings always draw logical inferences from the data they have before them, and if they act in accordance with such inferences, then we are left with nothing but logical conduct, and it is ideas that "govern or upset the world." There is no room left for those sentiments to which Spencer was disposed to attribute that capacity; there is no way for them to crowd into a ready-made aggregate composed of experimental facts, however badly observed, and of logical inferences derived from such facts.

291. The principle advanced by Spencer makes sociology very easy, especially if it be combined with two other Spencerian principles: unitary evolution, and the identity, or quasi-identity, of the savages of our time with primitive man (§§ 728, 731). Accounts by travellers, more or less accurate and more or less soundly interpreted, give us, Spencer thinks, the data that primitive man had at his disposal; and where such accounts fail, we fill in the gaps with our imagination, which, when it cannot get the real, takes the plausible. That gives us all we need for a sociology, for we have only to determine the logical implications of the data at hand, without wasting too much time on long and difficult historical researches.

292. In just that way Spencer sets about discovering the origin and evolution of religion. His primitive man is like a modern scientist working in a laboratory to frame a theory. Primitive man of course has very imperfect materials at his disposal. That is why, despite his logical thinking, he can reach only imperfect conclusions. All the same he gets some philosophical notions that are not a little subtle. Spencer, Ibid., Vol. I, § 154, represents as a "primitive" idea the notion that "any property characterizing an aggregate inheres in all parts of it." If you are desirous of testing the validity of that theory you need only state the proposition to some moderately educated individual among your friends, and you will see at once that he will not have the remotest idea of what you are talking about. Yet Spencer, loc. cit., believes that your friend will go on and draw logical conclusions from something he does not understand: "The soul, present in the body of the dead man preserved entire, is also present in preserved parts of his body. Hence the faith in relics." Surely Spencer could never have discussed that subject with some good Catholic peasant woman on the Continent. The argument he maps out might possibly lead a philosopher enamoured of logic to believe in relics, but it has nothing whatever to do with popular beliefs in relics.

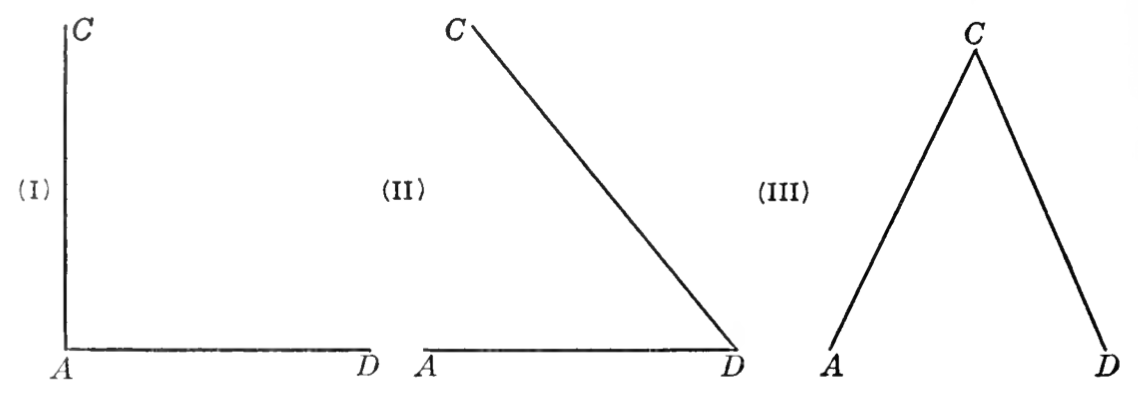

293. So Spencer's procedure has points of similarity with Comte's procedure. In general terms, one might state the situation in this fashion: we have two things, P and Q (Figure 8), that have to be considered in determining the social order R. We begin by asserting that Q alone determines that order; then we show that P determines Q. So Q is eliminated, and P alone determines the social order.

294. If Q designates "ideas" and P "sentiments," we get, roughly, the evolution of Comte's theories. If Q designates "sentiments" and P "ideas," we get, roughly, the evolution of Spencer's theories.

295. That is confirmed by the remarks of John Stuart Mill on the controversy between Comte and Spencer. Says he:1 "It will not be found, on a fair examination of what M. Comte has written, that he has overlooked any of the truth that there is in Mr. Spencer's theory. He would not indeed have said (what Mr. Spencer apparently wishes us to say) that the effects which can be historically traced, for example, to religion, were not produced by the belief in God, but by reverence and fear of Him. He would have said that the reverence and fear presuppose the belief: that a God must be believed in before he can be feared or reverenced." That is the very procedure in question! P is the belief in God; Q, sentiments of fear and reverence; P produces Q, and so becomes the cause determining conduct!

296. To a perfect logician like Mill it seems absurd that anyone could experience fear unless the feeling be logically inferred from a subject capable of inspiring fear. He should have remembered the verse of Statius,

"Primus in orbe deos fecit timor,"1and then he would have seen that a course diametrically opposite is perfectly conceivable.2 That granted, what was the course pursued in reality? Or better, what were the various courses pursued? It is for historical documents to answer, and we cannot let our fancy take the place of documents and pass off as real anything that seems plausible to us. We have to know how things actually took place, and not how they should have taken place, in order to satisfy a strictly logical intelligence.3

297. In other connexions, Mill is perfectly well aware of the social importance of non-logical actions. But he at once withdraws the concession, in part at least, and instead of going on with what is, turns to speculations as to what ought to be. That is the general procedure; and many writers resort to it to be rid of non-logical conduct.

298. In his book On Liberty, p. 16, Mill writes, for example: "Men's opinions . . . on what is laudable or blameable, are affected by all the multifarious causes which influence their wishes in regard to the conduct of others, and which are as numerous as those which determine their wishes on any other subject: sometimes their reason—at other times their prejudices or superstitions: often their social affections, not seldom their antisocial ones, their envy or jealousy, their arrogance or contemptuousness: but most commonly, their desires or fears for themselves—their legitimate or illegitimate self-interest. Wherever there is an ascendant class, a large portion of the morality of the country emanates from its class interests, and its feelings of class superiority."

All that, with a few reservations, is well said and approximately pictures the facts.1 Mill might have gone on in that direction, and inquired, since he was dealing with liberty, into the relations of liberty to the motives he assigns to human conduct. In that event, he might have made a discovery: he might have seen that he was involved in a contradiction in trying with all his might to transfer political power to "the greatest number," while at the same time defending a "liberty" that was incompatible with the prejudices, sentiments, and interests of said "greatest number." That discovery would then have enabled him to make a prophecy—one of the fundamental functions of science; namely, to foresee that liberty, as he conceived it, was progressively to decline, as being contrary to the motives that he had established as determinants of the aspirations of the class which was about to become the ruling class.

299. But Mill thought less of things as they are than of things as they ought to be. He says, Ibid., p. 22: "He [a man] cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise."1

That may be a "good justice," but it is not the justice handed out to us by our masters, who each year favour us with new laws to prevent our doing the very things that Mill says people should be allowed to do. His preaching, therefore, has been altogether without effect.

300. In certain writers the part played by non-logical actions is suppressed altogether, or rather, is regarded merely as the exceptional part, the "bad" part. Logic alone is a means to human progress. It is synonymous with "good," just as all that is not logical is synonymous with "evil." But let us not be led astray by the word "logic." Belief in logic has nothing to do with logico-experimental science; and the worship of Reason may stand on a par with any other religious cult, fetishism not excepted.

301. Condorcet expresses himself as follows:1 "So a general knowledge of the natural rights of man; the opinion, even, that such rights are inalienable and unprescribable; a prayer voiced aloud for liberty of thought and press, for freedom of commerce and industry, for succour of the people . . . indifference to all religions —classified, at last, where they belong with superstitions and political devices [The good soul fails to notice that his worship of Progress is itself a religion!]—hatred and hypocrisy and fanaticism; contempt for prejudices; zeal for the propagation of enlightenment—all became the common avowal, the distinguishing mark, of anyone who was neither a Machiavellian nor a fool." Preaching religious toleration, Condorcet is not aware that he is betraying an intolerance of his own when he treats dissenters from his religion of Progress the way the orthodox have always treated heretics. It is true that he considers himself right and his adversaries wrong, because his own religion is good and theirs bad; but that, inverting terms, is exactly what they say too.

302. Maxims from Condorcet and other writers of his time are still quoted by humanitarian fanatics today. Condorcet continues, p. 292: "All errors in politics and morals are based on philosophical errors, which are in turn connected with errors in physic. There is no religious system, no supernatural extravagance, that is not grounded on ignorance of the laws of nature." But he himself gives proof of just such ignorance when he tries to have us swallow absurdities like the following, p. 345: "What vicious practice is there, what custom contrary to good faith, nay, what crime, that cannot be shown to have its cause and origin in the laws, the institutions, the prejudices, of the country in which that practice, that custom, is observed, that crime committed?" And he concludes finally, p. 346, that "nature links truth, happiness, and virtue with chain unsunderable."

303. Similar ideas are common among the French philosophes of the later eighteenth century. In their eyes every blessing doth from "reason" flow, every ill from "superstition." Holbach sees the source of all human woe in error;1 and that belief has endured as one of the dogmas of the humanitarian religion, holiest of holies, of which our present-day "intellectuals" form the priesthood.2

304. All these people fail to notice that the worship of "Reason," "Truth," "Progress," and other similar entities is, like all cults, to be classed with non-logical actions. It was born, it has flourished, and it continues to prosper, for the purpose of combating other cults, just as in Graeco-Roman society the oriental cults arose out of opposition to the polytheistic cult. At that time one same current of non-logical conduct found its multiple expression in the taurobolium, the criobolium, the cult of Mithras, the growing importance of mysteries, Neo-Platonism, mysticism, and finally Christianity, which was to triumph over rival cults, none the less borrowing many things from them. So, toward the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, one same current of non-logical conduct finds its expression in the theism of the philosophes, the sentimental vagaries of Rousseau, the cult of "Reason" and the "Supreme Being," the love of the First Republic for the number 10, theophilanthropy (of which the "positivist" religion of Comte is merely an offshoot), the religion of Saint-Simon, the religion of pacifism, and other religions that still survive to our times.

These considerations belong to a much more comprehensive order, properly relating to the subjective aspect of theories indicated in § 13. In general, in other words, we have to ask ourselves why and how individuals come to evolve and accept certain theories. And, in particular, now that we have identified one such purpose—the purpose of giving logical status to conduct that does not possess it—we have to ask by what means and devices that purpose is achieved. From the objective standpoint, the error in the arguments just noted lies in their giving an a priori answer to the questions stated in § 14, and in maintaining that a theory needs simply to be in accord with the facts to be advantageous to society. That error is usually supplemented by the further error of considering facts not as they stand in reality but as they are pictured by the exhilarated imagination of the enthusiast.

305. Our induction so far has shown from some few particular cases the prevalence of a tendency to evade consideration of non-logical actions, which nevertheless force themselves upon the attention of anyone undertaking to discuss human societies; and also the no mean importance of that tendency. Now we must look into it specially and in general terms.1

306. So let us now examine the various devices by which non-logical actions are eliminated so that only logical actions are left: and suppose we begin as usual by classifying the objects we are trying to understand.

The principles2 underlying non-logical actions are held to be devoid of any objective reality (§§ 307-18).

Genus I. They are disregarded entirely (§§ 307-08).

Genus II. They are regarded as absurd prejudices (§§ 309-11)

Genus III. They are regarded as tricks used by some individuals to deceive others (§§ 312-18)

The principles underlying non-logical actions are credited with now more, now less, objective reality (§§ 319-51)

Genus I. The principles are taken as completely and directly real (§§ 319-38)

Iα. Precepts with sanctions in part imaginary (§§ 321-33)

Iβ. Simple interposition of a personal god or a personified abstraction (§§ 332-33)

Iγ. The same interposition supplemented by legends and logical inferences (§ 334)

Iδ. Some metaphysical entity is taken as real (§§ 335-36)

Iε. What is real is an implicit accord between the principles and certain sentiments (§§ 337-38)

Genus II. The principles of non-logical conduct are not taken as completely or directly real. Indirectly, the reality is found in certain facts that are said to be inaccurately observed or imperfectly understood (§§ 339-50)

IIα. It is assumed that human beings make imperfect observations, and derive inferences from them logically (§§ 340-46)

IIβ. A myth is taken as the reflection of some historical reality that is concealed in one way or another, or else as a mere imitation of some other myth (§§ 347-49)

IIγ. A myth is made up of two parts: a historical fact and an imaginary adjunct (§ 350)

Genus III. The principles of non-logical actions are mere allegories (§§ 351-52)

It is assumed that non-logical actions have no effect on "progress," or else are obstructive to it. Hence they are to be eliminated in any study designed solely to promote "progress" (§§ 353-56).

307. Let us examine these various categories one by one.

Device A-I: Non-logical actions are disregarded. Non-logical actions can be disregarded entirely as having no place in the realm of reality. That is the position of Plato's Socrates in the matter of the national religions of Greece.1 He is asked what he thinks of the ravishing of Orithyia, daughter of Erechtheus, by Boreas. He begins by rejecting the logical interpretation that tries to see a historical fact in the myth (IIγ). Then he opines that such inquiries are as finespun as they are profitless, and falls back on the popular belief. On common belief the oracle at Delphi also relied when it prescribed that the best way to honour the gods was for each to follow the customs of his own city.2 Certainly the oracle in no wise meant by that that such customs corresponded to things that were not real; yet actually they might as well have, since they were held to be entirely exempt from the verification to which real things are considered subject. That method often amounts to viewing beliefs as non-logical actions to be taken for what they are without any attempt to explain them—the problem being merely to discover the relationship in which they stand towards other social facts. That, overtly or tacitly, is the attitude of many statesmen.

308. So, in Cicero's De natura deorum, the pontifex Cotta distinguishes the statesman from the philosopher. As pontifex he protests that he will ever defend the beliefs, the worship, the ceremonies, the religion, of the forefathers, and that no argument, be it of scholar or dunce, will ever budge him from that position. He is persuaded that Romulus and Numa founded Rome, the one with his auspices, the other with his religion. "That, Balbus, is what I think, as Cotta and as pontifex. It is now for me to know what you think. From you, a philosopher, I have a right to expect some reason for your beliefs. The beliefs I get from our forefathers I must accept quite apart from any proof."1 In that it is obvious that as pontifex Cotta deliberately steps aside from the realm of logical reality, which implies a belief either that traditional Roman beliefs have no basis in fact or else that they are to be classed with non-logical actions.2

309. Device A-II: The principles of non-logical actions are regarded as absurd prejudices. One may consider merely the forms of non-logical actions and finding them irrational, judge them absurd prejudices, at the most deserving of attention from a pathological standpoint as veritable maladies of the human race. That has been the attitude of not a few writers in dealing with legal and political formalities. It is the attitude especially of writers on religion and most of all of writers on forms of worship. It is also the attitude of our contemporary anti-clericals with regard to the Christian religion—and it betrays great ignorance on the part of those bigots, along with a narrow-mindedness that incapacitates them for ever understanding social phenomena.

We have already seen specimens of this type of reasoning in the works of Condorcet (§§ 301-02) and Holbach (§§ 2962, 303). A more diluted type is observable in disquisitions purporting to make this or that religion "more scientific" (§ 162), on the assumption that a religion which is not scientific is either absurd or reprehensible. So in earlier times there were efforts to remove by subtle interpretation such elements in the legends and cults of the pagan gods as were considered non-logical. It was the procedure of the Protestants during the Reformation, while the liberal Protestants of our day are repeating the same exploits, appealing to their pseudo-science. So also for the Modernists in their criticism of Catholicism, and for our Radical Socialists in their demeanour towards Marxism.

310. If one regards certain non-logical actions as absurd, one may centre chiefly on their ridiculous aspects; and that is often an effective weapon for combating a faith. Frequent use of it was made against established religions from the day of Lucian down to the day of Voltaire. In an article replete with historical blunders, Voltaire says of the religion of Rome: "I am imagining that after conquering Egypt Caesar sends an embassy to China, with the idea of stimulating the foreign trade of the Roman Empire. . . . The Emperor Iventi, first of that name, is reigning at the time. . . . After receiving Caesar's ambassadors with typical Chinese courtesy, he secretly inquires through his interpreters as to the civilization, customs, and religion of these Romans. . . . He learns that the Roman People supports at great expense a college of priests, who can tell you exactly the right time for embarking on a voyage and the very best place for fighting a battle by inspecting the liver of an ox or the appetite with which chickens eat their barley. That sacred science was brought to the Romans long, long before by a little god named Tages, who was unearthed somewhere in Tuscany. The Roman people worship just one god whom they always call 'Highest and Best.' All the same, they have built a temple to a harlot named Flora; and most Roman housewives have little household gods in their homes, five or six inches high. One of the little divinities is the goddess Nipples, another the god Bottom. . . . The Emperor has his laugh. The courts at Nanking at first conclude, as he does, that the Roman ambassadors are either lunatics or impostors . . . but the Emperor, being as just as he is courteous, holds private converse with the ambassadors. . . . They confess to him that the College of Augurs dates from early ages of Roman barbarism; that an institution so ridiculous has been allowed to survive only because it became endeared to the people in the course of long ages; that all respectable people make fun of the augurs; that Caesar never consults them; that according to a very great man by the name of Cato no augur is ever able to speak to a colleague without a laugh; and finally that Cicero, the greatest orator and best philosopher of Rome, has just published against the augurs a little essay, On Divination, in which he hands over to everlasting ridicule all auspices, all prophecy, and all the fortune-telling of which humanity is enamoured. The Emperor of China is curious to read Cicero's essay. His interpreters translate it. He admires the book and the Roman Republic."1

311. In dealing with writings of this kind, we must be careful not to fall into the very error we are here considering, with reference to non-logical actions.1 The intrinsic value of such satires may be zero when viewed from the experimental standpoint, whereas their polemical value may be great. Those two things we must always keep distinct. Moreover they may have a certain intrinsic value: a group of non-logical actions taken as a whole may be useful for attaining a given purpose without absolutely all of them, taken individually, being useful to that purpose. Certain ridiculous actions may be eliminated from such a group without impairing its effectiveness. However, in so reasoning we must beware of falling into the fallacy of the man who said he could lose all his hair without becoming bald because he could lose any particular hair without suffering that catastrophe.

312. Device A-III: Non-logical actions as tricks for deceit. After establishing, as in the two cases above, that certain actions are not logical, but still resolved to have them such in the feeling that every human act should be born of logic, a writer may go on and say that an institution involving non-logical conduct is an invention of this or that individual or group that is designed to procure some personal advantage, or some advantage to state, society, or humanity at large. So actions intrinsically non-logical are transformed into actions that are logical from the standpoint of the end in view.

To adopt this procedure as regards actions deemed beneficial to society is to depart from the extreme case noted in § 14, where it is maintained that only theories which accord with facts (logico-experimental theories) can be beneficial to society. It is here recognized that there are theories which are not logico-experimental, but which are nevertheless beneficial to society. All the same, the writer cannot make up his mind to admit that such theories derive spontaneously from non-logical impulse. No, all conduct has to be logical. Therefore such theories too are products of logical actions. These actions cannot originate in the sources of the theories, since it has been recognized that the theories have no experimental basis; but they may envisage the same purposes as the theories, which experience shows are beneficial to society. So we get the following solution: "Theories not in accord with the facts may be beneficial to society and are therefore logically invented to that end."1

313. The notion that non-logical actions have been logically devised to attain certain purposes has been held by many many writers. Even Polybius, a historian of great sagacity, speaks of the religion of the Romans as originating in deliberate artifice.1 Yet he himself recognized that the Romans succeeded in creating their commonwealth not by reasoned choices but by allowing themselves to be guided by circumstances as they arose.2

314. We may take Montesquieu's view of Roman religion as the type of the interpretation here in question.1 "Neither fear nor piety established religion among the Romans, but the same necessity that compels all societies to have religions. . . . I note this difference, however, between Roman legislators and the lawgivers of other peoples, that the Romans created religion for the State, the others the State for religion. Romulus, Tatius, and Numa made the gods servants of statesmanship; and the cult and the ceremonies that they instituted were found to be so wise that when the kings were expelled the yoke of religion was the only one which that people dared not throw off in its frenzy for liberty. In establishing religion, Roman law-makers were not at all thinking of reforming morals or proclaiming moral principles. . . . They had at first only a general view, to inspire a people that feared nothing with fear of the gods, and to use that fear to lead it whithersoever they pleased. . . . It was in truth going pretty far to stake the safety of the State on the sacred appetite of a chicken and the disposition of the entrails in a sacrificial animal; but the founders of those ceremonies were well aware of their strong and weak points, and it was not without good reasons that they sinned against reason itself. Had that form of worship been more rational, the educated as well as the plain man would have been deceived by it; and so all the advantage to be expected from it would have been lost."

315. It is curious that Voltaire and Montesquieu followed opposite though equally mistaken lines, and that neither of them thought of a spontaneous development of non-logical conduct.

316. The variety of interpretation here in question sometimes contains an element of truth, not as regards the origin of non-logical actions, but as regards the purposes to which they may be turned once they have become customary. Then it is natural enough that the shrewd should use them for their own ends just as they use any other force in society. The error lies in assuming that such forces have been invented by design (§ 312). An example from our own time may bring out the point more clearly. There are plenty of rogues, surely, who make their profit out of spiritualism; but it would be absurd to imagine that spiritualism originated as a mere scheme of rogues.

317. Van Dale, in his treatise De Oraculis, saw nothing but artifice in the pagan oracles. That notion belongs with this group of interpretations. Eusebius wavers between it and the view that oracles were the work of devils.1 Such mixtures of interpretations are common. We shall come back to them.

318. Likewise with this variety are to be classed interpretations that regard non-logical actions as consequences of an external or exoteric doctrine serving to conceal an internal or esoteric doctrine. That would make actions which are non-logical in appearance logical in reality. Consider a passage in Galileo's Dialogue of the Greater Systems (Salviati speaking):1 "That the Pythagoreans held the science of numbers in very high esteem . . . I am well aware, nor would I be loath to concur in that judgment. But that the mysteries in view of which Pythagoras and his sect held the science of numbers in such great veneration are the absurdities commonly current in books and conversation, I can in no way agree. On the contrary, they did not care to have their wonders exposed to the ridicule and disparagement of the common herd. So they damned as sacrilegious any publication of the more recondite properties of the numbers and incommensurable and irrational quantities with which they dealt, and they preached that anyone disclosing such things would suffer torment in the world to come. I think that some of them, to throw a sop to the vulgar and be free of prying importunity, represented their numeral mysteries as the same childish idiocies that later on spread generally abroad. It was a shrewd and cunning device on their part, like the trick of that sagacious young man who escaped the prying of his mother (or his curious wife—I forget which), who was pressing him to confide the secrets of the Senate, by making up a story wherewith she and other prattling females proceeded to make fools of themselves, to the great amusement of the Sentaors."

That the Pythagoreans sometimes misrepresented their own doctrines seems certain; but it is not at all apparent that that was the case with their ideas on perfect numbers. On that point Galileo is mistaken (§§ 960 f.).

319. Device B-I: The principles are taken as completely and directly real.1 This variety is exemplified by non-logical actions of a religious character on the part of unquestioning believers. Such actions differ little if at all from logical actions. If a person is convinced that to be sure of a good voyage he must sacrifice to Poseidon and sail in a ship that does not leak, he will perform the sacrifice and caulk his seams in exactly the same spirit.

320. Curiously enough, such doctrines come closer than any others to a scientific status. They differ from the scientific, in fact, only by an appendage that asserts the reality of an imaginary principle; whereas many other doctrines, in addition to possessing the same appendage, further differ from scientific doctrines by inferences that are either fantastic or devoid of all exactness.

321. Device B-Iα: Precept plus sanction. This variety is obtained by appending some adjunct or other to the simple sanctionless precept—to the taboo (cf. § 154).1

322. Reinach writes:1 "A taboo is an interdiction; an object that is taboo, or tabooed, is a forbidden object. The interdiction may forbid corporal contact or visual contact; it may also exempt the object from the peculiar kind of violation involved in pronouncing its name. . . . Similar interdictions are observable in Greece and Rome, and among many other peoples, where generally it is explained that knowledge of a name enables a person to 'evoke' with evil intent the 'power' that the name designates. That explanation may have been valid at certain periods; but it does not represent the primitive state of mind. Originally it was the sanctity of the name itself that was dreaded, on the same grounds as contact with a tabooed object."

Reinach is right in regarding as an appendage the notion that knowledge of the name of an object gives a person power over it; but the notion of sanctity is likewise an appendage. Indeed, probably few of the individuals observing a taboo would know what was meant by an abstraction such as "sanctity." For them the taboo is just a non-logical action, just an aversion to touching, looking at, naming, the thing tabooed. Later on an effort is made to explain or justify the aversion; and then the mysterious power of which Reinach speaks (or perhaps his own notion of sanctity) is invented.

Reinach continues: "The notion of the taboo is narrower still than the notion of interdiction. The characteristic difference is that the taboo never gives a reason." That is excellent! The non-logical action has just that trait. But for that very reason Reinach should not, in a particular case, provide the taboo with a reason in some consideration of sanctity. He goes on: "The prohibition is merely stated, taking the cause for granted—it is, in fact, nothing but the taboo itself, that is to say, the assertion of a mortal peril." But in saying that he is withdrawing his concession and trying to edge back into the domain of logic. No "cause" is taken for granted! The taboo lies in a pure and absolute repugnance to doing a certain thing. To get something similar from our own world: There is the sentimental person who could never be induced to cut off a chicken's head. There is no "cause" for the aversion; it is just an aversion, and it is strong enough to keep the person from cutting off a chicken's head! It is not apparent either why Reinach would have it that the penalty for violating a taboo is always a mortal peril. He himself gives examples to the contrary. Going on, he returns to the domain of non-logical actions, well observing that "the taboos that have come down into contemporary cultures are often stated with supporting reasons. But such reasons have been excogitated in times relatively recent [One could not say better.] and bear the stamp of modern ideas. For example, people will say, 'Speak softly in a chamber of death [A taboo that gives no evidence of having a "mortal peril" for a sanction.] out of respect for the dead.' The primitive taboo lay in avoiding not only contact with a corpse, but its very proximity. [Still no evidence of any mortal peril.] Nevertheless even today, in educating children taboos are imparted without stated reasons, or else with some mere specification of the general character of the interdiction: 'Do not take off your coat in company, for that is not nice.' In his Works and Days, v. 727, Hesiod interdicts passing water with one's face towards the sun, but he gives no reasons for the prohibition. [A pure non-logical action.] Most taboos relating to decorum have come down across the centuries without justifications" [and with no threats of "mortal peril"].2

323. With taboos may profitably be classed other things of the kind where logical interpretation is reduced to a minimum. William Marsden says of the Mohammedans of Sumatra:1 "Many who profess to follow it [Mohammedanism] give themselves not the least concern about its injunctions, or even know what they require. A Malay at Marina upbraided a countryman, with the total ignorance of religion, his nation laboured under, 'You pay a veneration to the tombs of your ancestors: what foundation have you for supposing that your dead ancestors can lend you assistance?' 'It may be true,' answered the other; 'but what foundation have you, for expecting assistance from Allah and Mahomet?' 'Are you not aware,' replied the Malay, 'that it is written in a Book? Have you not heard of the Koraan?' The native of the Passumah, with conscious inferiority, submitted to the force of this argument."2 That is a seed which will sprout and yield an abundant harvest of logical interpretations, some of which we shall find in the devices hereafter following.

324. Something like the taboo is the precept (§§ 154, 1480 f.). It may be given without sanction, "Do so and so," and in that form it is a plain non-logical action. In the injunction, "You ought to do so and so," there is a slight, sometimes a very slight, trace of explanation. It lurks in the term "ought," which suggests the mysterious entity Duty. That is often supplemented by a sanction real or imaginary, and then we get actions that are either actually logical or else are merely made to appear so. Only a certain number of precepts, therefore, can be properly grouped with the things we are classifying here.

325. In general, precepts may be distinguished as follows:

a. Pure precept, without stated reasons, and without proof. The proposition is not elliptical. No proof is given, either because no proof exists or because none is asked for. That, therefore, is the pure non-logical action. But human beings have such a passion for logical explanations that they usually stick one or two on, no matter how silly. "Do that!" is a precept. If it be asked, "Why should I do that?" the answer is, let us say, "Because . . . !" or, "Because it is customary." The logical appendage is of little value, except where violation of custom implies some penalty—but in that case the penalty, not the custom, carries the logical force.

326. b. The demonstration is elliptical. The proof, valid or not, is available. It has not been mentioned, but it may be. The proposition is a precept only in appearance. The terms "ought," "must," and the like may be suppressed, and the precept reduced to an experimental or pseudo-experimental theorem, the consequence deriving from the act without any interposition from without. This type of precept runs, "To get A, you must do B,"; or, negatively, "To avoid A, you must refrain from doing B." The first proposition can be stated thus: "When B is done, A results." Similarly for the second.

327. If both A and B are real things and if the nexus between them is actually logico-experimental, we get scientific propositions. They have nothing to do with the things we are trying to classify here. If the nexus is not logico-experimental, they are pseudo-scientific propositions, and a certain number of them are used to logicalize non-logical actions. For instance, if A stands for a safe voyage and B for sacrifices to Poseidon, the nexus is imaginary, and the non-logical action B is justified by the nexus that connects it with A. But if A stands for a safe voyage and B for defective ship-building, we get just an erroneous scientific proposition. A mistake in engineering is not a non-logical action.

328. If A and B are both imaginary, we are wholly outside the experimental field, and we need not consider such propositions. If A is imaginary and B real, we get non-logical actions, B, justified by the pretext, A.

329. c. The proposition is really a precept, but a real sanction enforced by an extraneous and real cause is appended to it. That gives a logical action: the thing is done to escape the sanction.

330. d. The proposition is a precept, but the sanction is imaginary, or enforcible only by an imaginary power. We get a non-logical action justified by the sanction.1

331. The terms of ordinary speech rarely have sharply defined meanings. The term "sanction" may be used more or less loosely. Here we have taken it in the strict sense. Broadly speaking, one might say that a sanction is always present. In the case of a scientific proposition the sanction might be the pleasure of reasoning soundly or the pain of reasoning amiss. But to go into such niceties would be just a waste of time.

332. Device B-Iβ: Introduction of a divinity or of personified abstractions. A very simple elaboration of the taboo, or pure precept, is involved in the introduction of a personal god, or of personifications such as Nature, by will of which non-logical actions are required of human beings and are therefore logicalized. How the requirement arises is often left dark. "A god (or Nature) wills that so and so be done." "And if it is not done?" The question remains unanswered. But very often there is an answer; it is asserted that the god (or Nature) will punish violators of the precept. In such a case we get a sanctioned precept of the species d above.

333. When the Greeks said that "strangers and beggars come from Zeus,"1 they were merely voicing their inclination to be hospitable to visitors, and Zeus was dragged in to give a logical colouring to the custom, by implying that the hospitality was offered either in reverence for Zeus, or to avoid the punishment that Zeus held in store for violators of the precept.

334. Device B-Iγ: Divinities plus legend and logical elaboration. Rare the case where such embellishments are not supplemented by multiple legends and logical elaborations; and through these new adjuncts we get mythologies and theologies that carry us farther and farther away from the concept of non-logical conduct. It may be worth while to caution that theologies at all complicated belong to restricted classes of people only. With them we depart from the field of popular interpretations and enter an intellectual or scholarly domain. To the variety in question here belong the interpretations of the Fathers of the Christian Church, such as the doctrine that the pagan gods were devils.

335. Device B-Iδ: Metaphysical entities taken as real. Here reality is ascribed not to a personal god or to a personification, but to a metaphysical abstraction. "The true," "the beautiful," "the good," "the honest," "virtue," "morality," "natural law," "humanity," "solidarity," "progress," or their opposite abstractions, enjoin or forbid certain actions, and the actions become logical consequences of the abstractions.1