145. So far we have stated our attitude in writing these volumes and the field in which we intend to remain. Now we are to study human conduct, the states of mind to which it corresponds and the ways in which they express themselves, in order to arrive eventually at our goal, which is to discover the forms of society. We are following the inductive method. We have no preconceptions, no a priori notions. We find certain facts before us. We describe them, classify them, determine their character, ever on the watch for some uniformity (law) in the relationships between them. In this chapter we begin to interest ourselves in human actions.1

146. This is the first step we take along the path of induction. If we were to find, for instance, that all human actions corresponded to logico-experimental theories, or that such actions were the most important, others having to be regarded as phenomena of social pathology deviating from a normal type, our course evidently would be entirely different from what it would be if many of the more important human actions proved to correspond to theories that are not logico-experimental.

147. Let us accordingly examine actions from the standpoint of their logico-experimental character. But in order to do that we must first try to classify them, and in that effort we propose to follow the principles of the classificalion called natural in botany and zoology, whereby objects on the whole presenting similar characteristics are grouped together. In the case of botany Tournefort's classification was very wisely abandoned. It divided plants into "herbs" and "trees," and so came to separate entities that as a matter of fact present close resemblances. The so-called natural method nowadays preferred does away with all divisions of that kind and takes as its norm the characteristics of plants in the mass, putting like with like and keeping the unlike distinct. Can we find similar groupings to classify the actions of human beings?

148. It is not actions as we find them in the concrete that we are called upon to classify, but the elements constituting them. So the chemist classifies elements and compounds of elements, whereas in nature what he finds is mixtures of compounds. Concrete actions are synthetic—they originate in mixtures, in varying degrees, of the elements we are to classify.

149. Every social phenomenon may be considered under two aspects: as it is in reality, and as it presents itself to the mind of this or that human being. The first aspect we shall call objective, the second subjective (§§ 94 f.). Such a division is necessary, for we cannot put in one same class the operations performed by a chemist in his laboratory and the operations performed by a person practising magic; the conduct of Greek sailors in plying their oars to drive their ship over the water and the sacrifices they offered to Poseidon to make sure of a safe and rapid voyage. In Rome the Laws of the XII Tables punished anyone casting a spell on a harvest. We choose to distinguish such an act from the act of burning a field of grain.

We must not be misled by the names we give to the two classes. In reality both are subjective, for all human knowledge is subjective. They are to be distinguished not so much by any difference in nature as in view of the greater or lesser fund of factual knowledge that we ourselves have. We know, or think we know, that sacrifices to Poseidon have no effect whatsoever upon a voyage. We therefore distinguish them from other acts which (to our best knowledge, at least) are capable of having such effect. If at some future time we were to discover that we have been mistaken, that sacrifices to Poseidon are very influential in securing a favourable voyage, we should have to reclassify them with actions capable of such influence. All that of course is pleonastic. It amounts to saying that when a person makes a classification, he does so according to the knowledge he has. One cannot imagine how things could be otherwise.

150. There are actions that use means appropriate to ends and which logically link means with ends. There are other actions in which those traits are missing. The two sorts of conduct are very different according as they are considered under their objective or their subjective aspect. From the subjective point of view nearly all human actions belong to the logical class. In the eyes of the Greek mariners sacrifices to Poseidon and rowing with oars were equally logical means of navigation. To avoid verbosities which could only prove annoying, we had better give names to these types of conduct.1 Suppose we apply the term logical actions to actions that logically conjoin means to ends not only from the standpoint of the subject performing them, but from the standpoint of other persons who have a more extensive knowledge—in other words, to actions that are logical both subjectively and objectively in the sense just explained. Other actions we shall call non-logical (by no means the same as "illogical"). This latter class we shall subdivide into a number of varieties.

151. A synoptic picture of the classification will prove useful:

| Genera and species | Have the actions logical ends and purposes? | |

|---|---|---|

| Objectively? | Subjectively? | |

| Class I: Logical actions | ||

| (The objective end and the subjective purpose are identical.) | ||

| Yes | Yes | |

| Class II: Non-logical actions | ||

| (The objective end differs from the subjective purpose.) | ||

| Genus 1 | No | No |

| Genus 2 | No | Yes |

| Genus 3 | Yes | No |

| Genus 4 | Yes | Yes |

| Species of the genera 3 and 4 | ||

| 3α, 4α | The objective end would be accepted by the subject if he knew it. | |

| 3β, 4β | The objective end would be rejected by the subject if he knew it. | |

The ends and purposes here in question are immediate ends and purposes. We choose to disregard the indirect. The objective end is a real one, located within the field of observation and experience, and not an imaginary end, located outside that field. An imaginary end may, on the other hand, constitute a subjective purpose.

152. Logical actions are very numerous among civilized peoples. Actions connected with the arts and sciences belong to that class, at least for artists and scientists. For those who physically perform them in mere execution of orders from superiors, there may be among them non-logical actions of our II-4 type. The actions dealt with in political economy also belong in very great part in the class of logical actions. In the same class must be located, further, a certain number of actions connected with military, political, legal, and similar activities.

153. So at the very first glance induction leads to the discovery that non-logical actions play an important part in society. Let us therefore proceed with our examination of them.

154. First of all, in order to get better acquainted with these non-logical actions, suppose we look at a few examples. Many others will find their proper places in chapters to follow. Here are some illustrations of actions of Class II:

Genera 1 and 3, which have no subjective purpose, are of scant importance to the human race. Human beings have a very conspicuous tendency to paint a varnish of logic over their conduct. Nearly all human actions therefore work their way into genera 2 and 4. Many actions performed in deference to courtesy and custom might be put in genus 1. But very very often people give some reason or other to justify such conduct, and that transfers it to genus 2. Ignoring the indirect motive involved in the fact that a person violating common usages incurs criticism and dislike, we might find a certain number of actions to place in genera 1 and 3.

Says Hesiod:1 "Do not make water at the mouth of a river emptying into the sea, nor into a spring. You must avoid that. Do not lighten your bowels there, for it is not good to do so." The precept not to befoul rivers at their mouths belongs to genus 1. No objective or subjective end or purpose is apparent in the avoidance of such pollution. The precept not to befoul drinking-water belongs to genus 3. It has an objective purpose that Hesiod may not have known, but which is familiar to moderns: to prevent contagion from certain diseases.

It is probable that not a few actions of genera 1 and 3 are common among savages and primitive peoples. But travellers are bent on learning at all costs the reasons for the conduct they observe. So in one way or another they finally obtain answers that transfer the conduct to genera 2 and 4.

155. Granting that animals do not reason, we can place nearly all their so-called instinctive acts in genus 3. Some may even go in 1. Genus 3 is the pure type of the non-logical action, and a study of it as it appears in animals will help to an understanding of non-logical conduct in human beings.

Of the insects called Eumenes (pseudo-wasps) Blanchard writes that, like other Hymenoptera, they "suck the nectar of flowers when they are full grown [but that] their larvae feed only upon living prey; and since, like the larvae of wasps and bees, they are apodal and incapable of procuring food, they would perish at once if left to themselves. What happens, then, may be foreseen. The mother herself has to procure food for her young. That industrious little animal, who herself lives only on the honey of flowers, wages war upon the tribe of insects to assure a livelihood for her offspring. In order to stock its nest with victuals, this Hymenopteron nearly always attacks particular species of insects, and it knows how to find such species without any trouble, though to the scientist who hunts for them they seem very rare indeed. The female stings her victims with her dart and carries them to her nest. The insect so smitten does not die at once. It is left in a deep coma, which renders it incapable of moving or defending itself. The larvae are hatched in close proximity to the provisions that have been laboriously accumulated by the mother, and find within their reach a food adapted to their needs and in quantities sufficient for their whole life as larvae. Nothing is more amazing than this marvellous foresight; and it is altogether instinctive, it would seem. In laying her eggs every female prepares food for young whom she will never see; for by the time they are hatched she will long since have ceased to live."1

Other Hymenoptera, the Cerceres, attack Coleoptera. Here the action, subjectively non-logical, shows a marvellous objective logic. Suppose we let Fabre speak for himself. He observes that, in order to paralyze its prey, the Hymenopteron has first to find Coleoptera either with three thoracic ganglia very close together, contiguous in fact, or with the two rear ganglia joined. "That, really, is the prey they need. These Coleoptera, with motor centres situated so close together as to touch, forming a single mass and standing in intimate mutual connexions, can thus be paralyzed at a single thrust; or if several stings are needed, the ganglia that require treatment will at least lie together under the point of the stinger." Further along: "Out of the vast numbers of Coleoptera upon which the Cerceres might inflict their depredations, only two groups, the weevils and the Buprestes, fulfil the indispensable conditions. They live far from infested and noisome places, for which, it may be, the fastidious huntress has an unconquerable repugnance. Their numerous representatives vary in size, proportionate to the sizes of the various pirates, who are thus free to select their victims at pleasure. They, more than all others, are vulnerable at the one point where the stinger of the Hymenopteron can penetrate with success: for at that point the motor centres of the feet and wings are concentrated in such a way as to be readily accessible to the stinger. These three thoracic ganglia of the weevil lie very close together, the last two touching. In the Buprestes the second and third ganglia blend in a single bulky mass a short distance from the first. Now it is the weevils and the Buprestes precisely, to the absolute exclusion of all other prey, that we find hunted by the eight species of Cerceres that lay in stores of Coleoptera."2

156. For that matter, a certain number of actions in animals evince reasoning of a kind, or better, a sort of adaptation of means to ends as circumstances change. Says Fabre, whom we quote at such length because he has studied the subject better than anybody else:1 "For instinct nothing is difficult, so long as the act does not extrude from the fixed cycle that is the animal's birthright. For instinct also nothing is easy if the act has to deviate from the rut habitually followed. The insect that amazes for its high perspicacity will an instant later, when confronted with the simplest situation foreign to its ordinary practice, astound for its stupidity. . . . Distinguishable in the psychic life of the insect are two wholly different domains. The one is instinct proper, the unconscious impulse that guides the animal in the marvellous achievements of its industry. . . . It is instinct, and nothing but instinct, that makes a mother build a nest for a family she will never know, which counsels a supply of food for an unknowable posterity, which steers the dart toward the nerve-centre of the prey . . . with a view to keeping provisions fresh. . . . But for all of its unbending, unconscious cleverness, pure instinct, all by itself, would leave the insect disarmed in its perpetual battle with circumstance. . . . A guide is necessary to devise, accept, refuse, select, prefer this, ignore that—in a word, take advantage of the usables occasion offers. Such a guide the insect certainly has and even to a very conspicuous degree. It is the second domain of his psychic life. In it he is conscious and teachable by experience. Not daring to call that rudimentary aptitude intelligence, a title too exalted for it, I will call it discernment."

157. Qualitatively (§ 1441), phenomena are virtually the same in human beings; but quantitatively, the field of logical behaviour, exceedingly limited in the case of animals, becomes very far-reaching in mankind. All the same, many many human actions, even today among the most civilized peoples, are performed instinctively, mechanically, in pursuance of habit; and that is more generally observable still in the past and among less civilized peoples. There are cases in which it is apparent that the effectiveness of certain rites is believed in instinctively, and not as a logical consequence of the religion that practises them (§ 952). Says Fabre:1

"The various instinctive acts of insects are therefore inevitably linked together. Because a certain thing has just been done, another must unavoidably be done to complete it or prepare the way for its completion [That is the case with many human actions also.], and the two acts are so strictly correlated that the performance of the first entails the performance of the second, even when by some fortuitous circumstance the second may have become not only unseasonable, but at times even contrary to the animal's interests."

But even in the animal one detects a seed of the logic that is to come to such luxuriant flower in the human being. After describing how he tricked certain insects that obstinately persisted in useless acts, Fabre adds: "But the yellow-winged Sphex does not always let himself be fooled by the game of pulling his cricket away. There are chosen clans in his tribe, families of brainy wit, that, after a few disappointments, perceive the wiles of the trickster and find ways to checkmate them. But such revolutionaries, candidates for progress, are the small minority. The rest, stubborn conservators of the good old-fashioned ways, are the hoi polloi, the majority."

This remark should be remembered, for the conflict between a tendency to combinations, which is responsible for innovations, and a tendency to permanence in groups of sensations, which promotes stability, may put us in the way of explaining many things about human societies (Chapter XII).

158. The formation of human language is no whit less marvellous than the instinctive conduct of insects. It would be absurd to claim that the theory of grammar preceded the practice of speech. It certainly followed, and human beings have created most subtle grammatical structures without any knowledge of it.

Take the Greek language as an example. If one chose to go farther back to some Indo-European language from which Greek would be derived, our contentions would hold a fortiori, because the chance of any grammatical abstraction would be less and less probable. We cannot imagine that the Greeks one day got together and decided what their system of conjugation was to be. Usage alone made such a masterpiece of the Greek verb. In Attic Greek there is the augment, which is the sign of the past in historical tenses; and, for a very subtle nuance, besides the syllabic augment there is the temporal (quantitative) augment, which consists in a lengthening of the initial vowel. The conception of the aorist, and its functions in syntax, are inventions that would do credit to the most expert logician. The large number of verbal forms and the exactness of their functions in syntax constitute a marvellous whole.1

159. In Rome, the general invested with the imperium had to take the auspices on the Capitol before he could leave the city. He could do that only in Rome. One cannot imagine that that provision had originally the political purpose that it eventually acquired.1 "As long as the extension of existing imperia depended exclusively upon the will of the comitia, no new ones carrying full military authority could be established except by taking the auspices on the Capitol—consequently by performing an act that lay within urban jurisdiction. . . . To organize another [taking of auspices] in defiance of the constitution would have implied transgressing bounds held in awe even by the of the sovereign People. No constitutional barrier to extraordinary military usurpations held its ground anywhere near as long as this guarantee that had been found in the regulation as to a general's auspices. In the end that regulation also lapsed, or rather was circumvented. In later times some piece of land or other situated outside of Rome was 'annexed' by a legal fiction to the city and taken as though located within the pomerium, and the required auspicium was celebrated there."

Later on Sulla not only abolished the guarantee of the auspices, but even rendered it inapplicable by an ordinance whereby the magistrate was obligated not to assume command till after the expiration of his year of service [as a magistrate]—at a time, that is, when [being in his proconsular province] he could no longer take the urban auspices. Now Sulla, a conservative, obviously had no intention of providing for the overthrow of his constitution in that way, any more than the older Romans, in establishing the requirement of auspices taken in the Urbs, were anticipating attacks upon the constitution of the Republic. In reality, in their case, we have a nonlogical action of our 4α type; and in the case of Sulla a non-logical action of our 4β type.

In the sphere of political economy, certain measures (for example, wage-cutting) of business men (entrepreneurs) working under conditions of free competition are to some extent non-logical actions of our 4β type, that is, the objective end does not coincide with the subjective purpose. On the other hand, if they enjoy a monopoly, the same measures (wage-cutting) become logical actions.2

160. Another very important difference between human conduct and the conduct of animals lies in the fact that we do not observe human conduct wholly from the outside as we do in the case of animals. Frequently we know the actions of human beings through the judgments that people pass upon them, through the impressions they make, and in the light of the motives that people are pleased to imagine for them and assign as their causes. For that reason, actions that would otherwise belong to genera 1 and 3 make their way into 2 and 4.

Operations in magic when unattended by other actions belong to genus 2. The sacrifices of the Greeks and Romans have to be classed in the same genus—at least after those peoples lost faith in the reality of their gods. Hesiod, Opera et dies, vv. 735-39, warns against crossing a river without first washing one's hands in it and uttering a prayer. That would be an action of genus 1. But he adds that the gods punish anyone who crosses a river without so washing his hands. That makes it an action of genus 2.

This rationalizing procedure is habitual and very wide-spread. Hesiod says also, vv. 780-82, that grain should not be sown on the thirteenth of a month, but that that day is otherwise very auspicious for planting, and he gives many other precepts of the kind. They all belong to genus 2. In Rome a soothsayer who had observed signs in the heavens was authorized to adjourn the comitia to some other day.1 Towards the end of the Republic, when all faith in augural science had been lost, that was a logical action, a means of attaining a desired end. But when people still believed in augury, it was an action of genus 4. For the soothsayers who, with the help of the gods, were so enabled to forestall some decision that they considered harmful to the Roman People, it belonged to our species 4α, as is apparent if one consider that in general such actions correspond, very roughly to be sure, to the provisions used in our time for avoiding ill-considered decisions by legislative bodies: requirements of two or three consecutive readings, of approvals by two houses, and so on.

Most acts of public policy based on tradition or on presumed missions of peoples or individuals belong to genus 4. William I, King of Prussia, and Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, both considered themselves "men of destiny." But William I thought his mission lay in promoting the welfare and greatness of his country, Louis Napoleon believed himself destined to achieve the happiness of mankind. William's policies were of the 4α type; Napoleon's, of the 4β.

Human beings as a rule determine their conduct with reference to certain general rules (morality, custom, law), which give rise in greater or lesser numbers to actions of our 4α and even 4β varieties.

161. Logical actions are at least in large part results of processes of reasoning. Non-logical actions originate chiefly in definite psychic states, sentiments, subconscious feelings, and the like. It is the province of psychology to investigate such psychic states. Here we start with them as data of fact, without going beyond that.

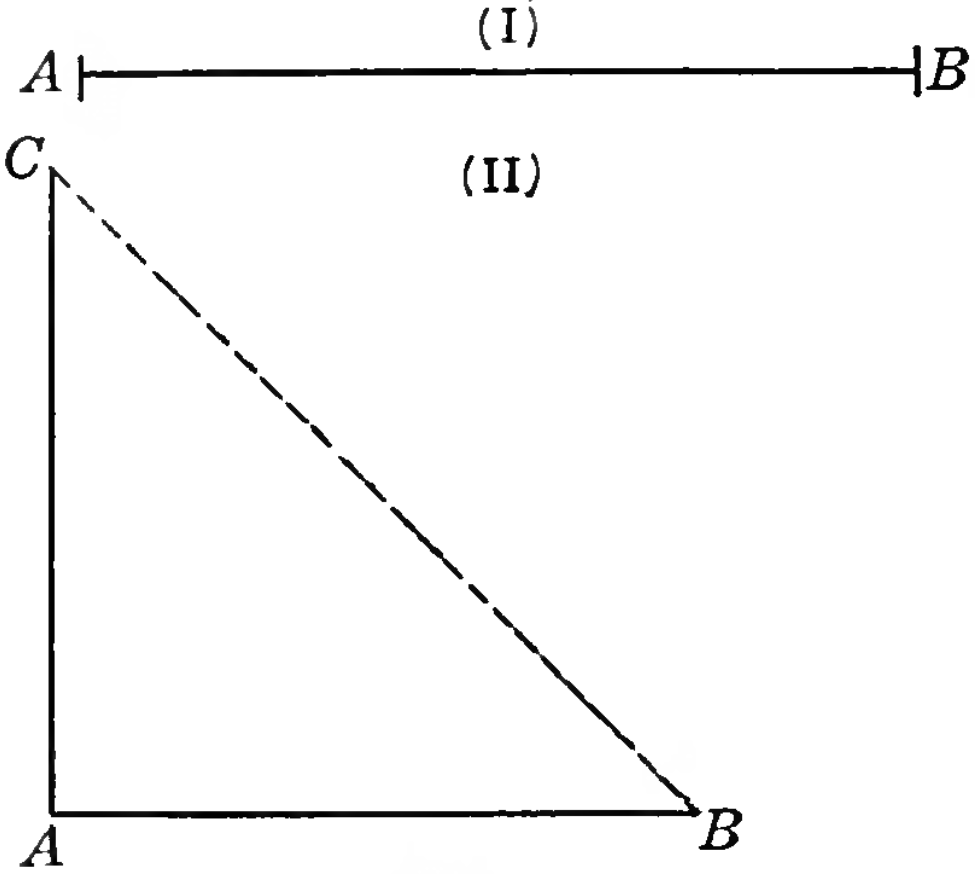

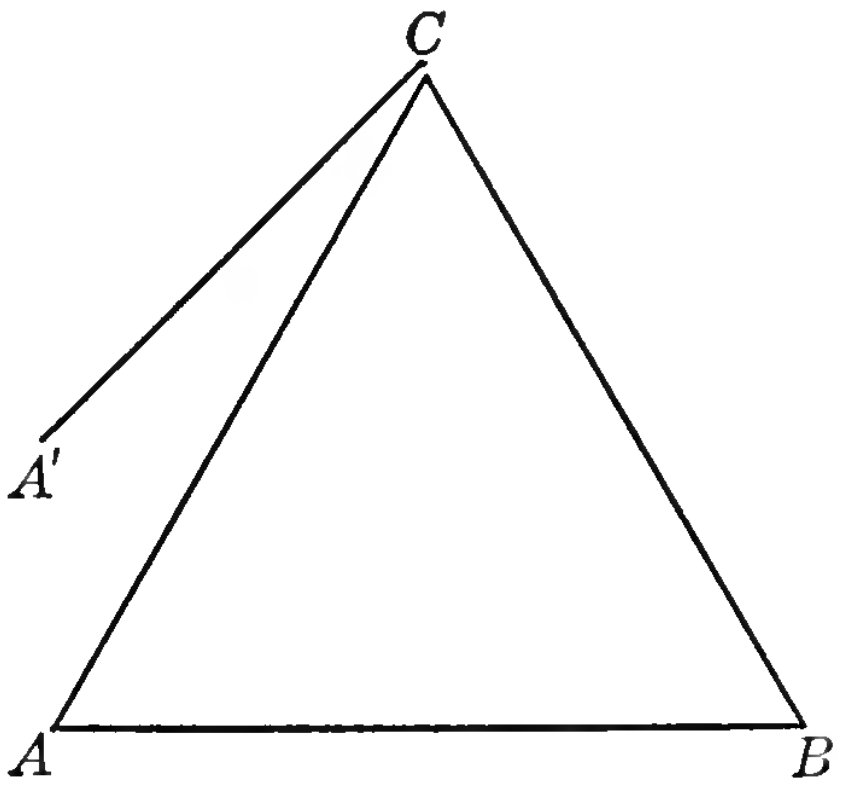

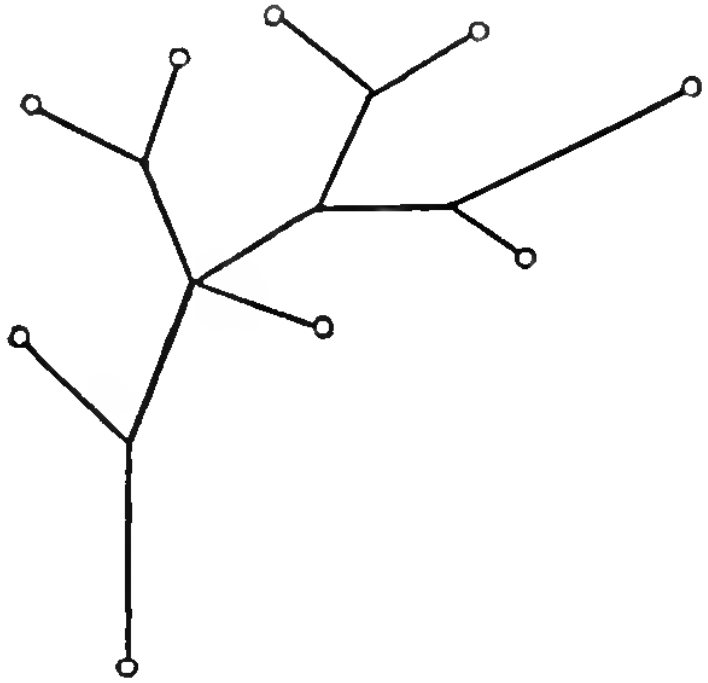

162. Thinking of animals, let us assume that the conduct B (I) in Figure 2, which is all we are in a position to observe, is connected with a hypothetical psychic state A (I). In human beings that psychic state is revealed not through the conduct B (II) alone, but also through expressions of sentiments, C, which often develop moral, religious, and other similar theories. The very marked tendency in human beings to transform non-logical into logical conduct leads them to imagine that B is an effect of the cause C. So a direct relationship, CB, is assumed, instead of the indirect relationship arising through the two relations AB, AC. Sometimes the relation CB in fact obtains, but not as often as people think. The same sentiment that restrains people from performing an act B (relation AB) prompts them to devise a theory C (relation AC). A man, for example, has a horror of murder, B, and he will not commit murder; but he will say that the gods punish murderers, and that constitutes a theory, C.

163. We are thinking not only of qualitative relations (§ 1441), but of quantitative also. Let us assume, for a moment, that a given force impelling a man to perform an act B has an index equivalent to 10 and that the man either performs or refrains from performing the act B according as the forces tending to restrain him have an index greater or smaller than 10. We shall then get the following alternatives:

Case 1. The restraining force of the association AB has an index greater than 10. In that situation it is strong enough to keep the man from performing the act. The association CB, if it exists, is superfluous.

Case 2. The restraining force of the association CB, if it exists, has an index larger than 10. In such a case, it is strong enough to prevent the act B, even if the force AB is equivalent to zero.

Case 3. The force resulting from the association AB has, let us say, an index equal to 4; and the force resulting from the association CB an index equal to 7. The sum of the indices is 11. The act, therefore, will not be performed. The force resulting from the association AB has an index equal to 2, the other retaining its index 7. The sum is 9; the act will be performed.

Suppose the association AB represents a person's aversion to performing the act B. AC represents the theory that the gods punish persons who commit the act B. Some people will abstain from doing B out of mere aversion to it (Case 1). Others refrain from it only because they fear the punishment of the gods (Case 2). Others still will forbear for both reasons (Case 3).

164. The following propositions are therefore false, because too absolute: "A natural disposition to do good is sufficient to restrain human beings from doing wrong." "Threat of eternal punishment is sufficient to restrain men from doing wrong." "Morality is independent of religion." "Morality is necessarily dependent on religion."

Suppose we say that C is a penalty threatened by law. The same sentiment that prompts people to establish the sanction restrains them from committing B. Some refrain from B because of their aversion to it; others in fear of the penalty C; still others for both reasons.

165. The relationships between A, B, C that we have just considered are fundamental, but they are far from being the only ones. First of all, the existence of the theory C reacts upon the psychic state A and in many many cases tends to re-enforce it. The theory consequently influences B, following the line CAB. On the other hand, the check B, which keeps people from doing certain things, reacts upon the psychic state A and consequently upon the theory C, following the line BAC. Then again the influence of C upon B influences A and so is carried back upon C. Suppose, for instance, a penalty C is considered too severe for a crime B. The infliction of such a penalty (CB) modifies the psychic state A, and as a consequence of the change, the penalty C is superseded by another more mild.

Change in a psychic state is first disclosed by an increase in certain crimes B. The increase in crime modifies the psychic state A, and the modification is translated into terms of a change in C.

Up to a certain point, the rites of worship in a religion may be comparable to the conduct B, its theology to the theory C. The two things both emanate from a certain psychic state A.

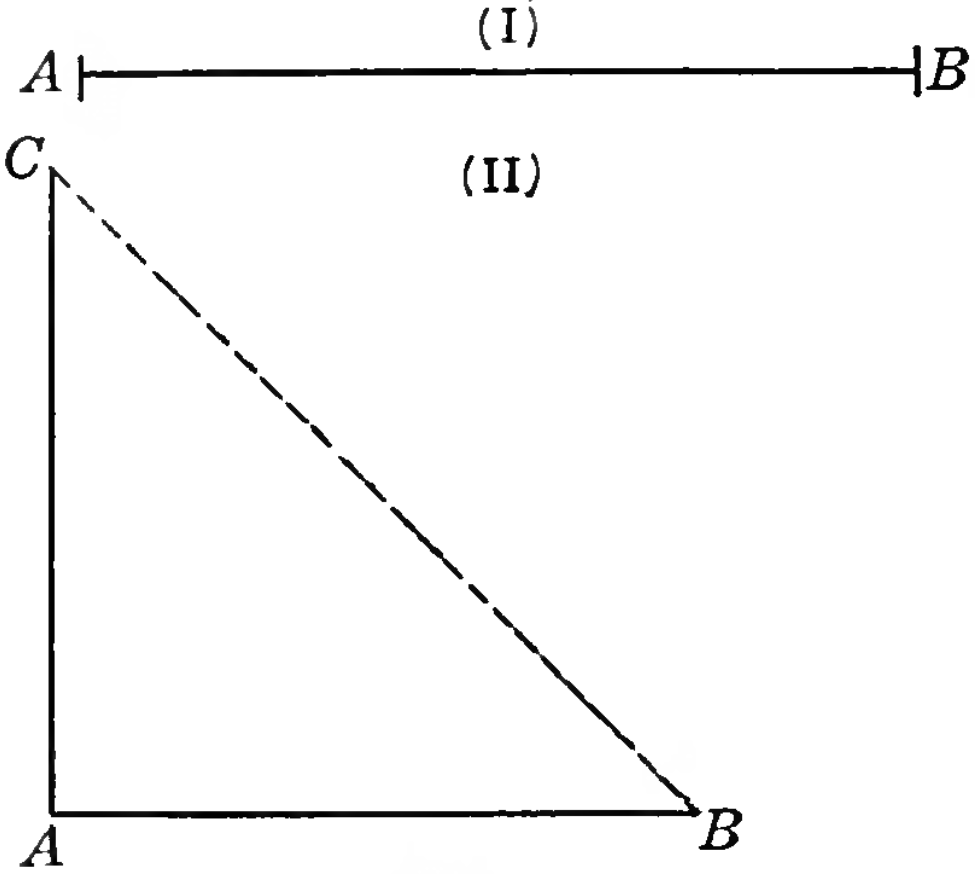

166. Let us consider certain conduct D (Figure 3), depending upon that psychic state, A. The rites of worship, B, do not influence D directly, but influence A and consequently D. In the same way they influence C and, vice versa, C influences B. There can in addition be a direct influence CD. The influence of the theology C upon A is usually rather weak, and consequently its influence upon D is also feeble, since the influence CD is itself usually slight. In general, then, we go very far astray in assuming that a theology, C, is the motive of the conduct, D. The proposition so often met with, "This or that people acts as it does because of a certain belief," is rarely true; in fact, it is almost always erroneous. The inverse proposition, "People believe as they do because of this or that conduct," as a rule contains a larger amount of truth; but it is too absolute, and has its modicum of error. Beliefs and conduct are not, to be sure, independent; but their correlation lies in their being, as it were, two branches of one same tree (§ 267).1

167. Before the invasion of Italy by the gods of Greece, the ancient Roman religion did not have a theology, C: it was no more than a cult, B. But the cult B, reacting upon A, exerted a powerful influence on the conduct, D, of the Roman people. Nor is that the whole story. The direct relation, BD, when it existed, looks to us moderns manifestly absurd. But the relation BAD may often have been very reasonable and very beneficial to the Roman people. Any direct influence of a theology, C, upon D is in general weaker even than its influence upon A. It is therefore a serious mistake to measure the social value of a religion strictly by the logical or rational value of its theology (§ 14). Certainly, if the theology becomes absurd to the point of seriously affecting A, it will for the same reason seriously affect D. But that rarely occurs. Only when the psychic state A has changed do people notice certain absurdities that previously had escaped them altogether.

These considerations apply to theories of all kinds.1 For example, C is the theory of free trade; D, the concrete adoption of free trade by a country; A, a psychic state that is in great part the product of individual interests, economic, political, and social, and of the circumstances under which people live. Direct relations between C and D are generally very tenuous. To work upon C in order to modify D leads to insignificant results. But any modification in A may react upon C and upon D. D and C will be seen to change simultaneously, and a superficial observer may think that D has changed because C has changed, whereas closer examination will reveal that D and C are not directly correlated, but depend both upon a common cause, A.

168. Theoretical discussions, C, are not, therefore, very serviceable directly for modifying D; indirectly they may be effective for modifying A. But to attain that objective, appeal must be made to sentiments rather than to logic and the results of experience. The situation may be stated, inexactly to be sure, because too absolutely, but nevertheless strikingly, by saying that in order to influence people thought has to be transformed into sentiment.

In the case of England, the continuous practice of free trade B (Figure 3) over a long period of years has in our day reacted upon the psychic state A (interests, etc.) and intensified it, so increasing obstacles in the way of introducing protection. The theory of free trade, C, is in no way responsible for that. However, other facts, such as growing needs on the part of the Exchequer, are nowadays tending to modify A in their turn; and such modifications may serve to change B and so bring protection about. Meantime modifications in C will be observable and new theories favourable to protection will come into vogue.

A theory, C, has logical consequences. A certain number of them are to be found present in B. Others are absent. That would not be the case if B were the direct consequence of C, for if it were, all the logical implications of C would appear in B without exception. But C and B are simply consequences of a certain psychic state, A. There is nothing therefore to require perfect logical correspondence between them. We shall always be on the wrong road, accordingly, when we imagine that we can infer B from C by establishing that correspondence logically. We are obliged, rather, to start with C and determine A, and then find a way to infer B from A. In doing that very serious difficulties are encountered; and unfortunately they have to be overcome before we can hope to attain scientific knowledge of social phenomena.

169. We have no direct knowledge of A. What we know is certain manifestations of A, such as C and B; and we have to get back from them to A. The difficulties are increased by the fact that though B is susceptible of exact observation, C is almost always stated in obscure terms altogether devoid of exactness.

170. The theory we have been thinking of is a popular theory, or at least, a theory held by large numbers of people. The case where C is a theory framed by scientists is in some respects similar, yet in other respects different.

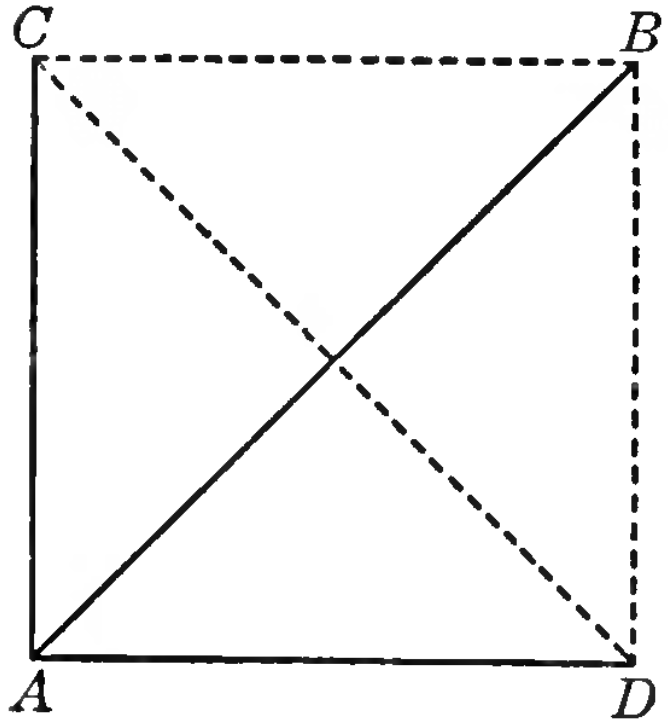

Unless the theory C is coldly scientific, C is affected by the psychic state of the scientists who frame it. If they belong to the group that has been performing the acts, B, their psychic state has—save in the very rare case of an individual not given to following the beaten path—something in common with the psychic state of the members of the group; and consequently A still influences C. That is all the case can have in common with the preceding case. If scientists are dealing with the conduct of people belonging to groups entirely different from their own—say with some foreign country, or some very different civilization, or with historical matters going back to a remote past—their psychic state, A' (Figure 4), is not identical with A. It may differ now more, now less, or even in some particular case be altogether different. Now it is the psychic state that influences C. So A may affect C very little, if at all. If we ignore all influences from A or A', we get interpretations of the facts, B, that are purely theoretical. If C is a strict and exact principle and is applied to B with faultless logic and without ambiguities of any kind, we get scientific interpretations.

171. But the class of theories that we are here examining includes others. C may be an uncertain principle, lacking in exactness, and sometimes even a principle of the experimental type. Furthermore, it may be applied to B with illogical reasonings, arguments by analogy, appeals to sentiment, nebulous irrelevancies. In such cases we get theories of little or no logico-experimental value, though they may have a great social value (§ 14). Such theories are very numerous, and we shall find them occupying much of our attention.1

172. Let us go back to the situation in Figure 3, and to get better acquainted with that subject, which is far from being an easy one to master, let us put abstractions aside and examine a concrete case. In that way we shall be led to follow certain inductions which arise spontaneously from the exposition of facts. Then we can go back to the general case and continue the study of which we have just sketched the initial outlines.

There is a very important psychic state that establishes and maintains certain relationships between sensations, or facts, by means of other sensations, P, Q, R. . . . Such sensations may be successive, and that, probably, is one of the ways in which instinct manifests itself in animals. On the other hand they may be simultaneous, or at least be considered such; and their union constitutes one of the chief forces in the social equilibrium.

Let us not give a name to that psychic state, in order, if possible, to avoid any temptation to derive the significance of the thing from the name we give it (§ 119). Let us continue to designate it simply by the letter A, as we have done for a psychic state in general. We shall have to think of the state not only as static, but also as dynamic. It is very important to know how the fundamental element in the institutions of a people changes. Case 1. It may change but reluctantly, slowly, showing a marked tendency to keep itself the same. Case 2. It may change readily, and to very considerable extents, but in different ways, as for instance: Case 2α. The form may change as readily as the substance—for a new substance, new forms. The sensations P, Q, R . . . may be easily disjoined, whether because the force X that unites them is weak, or because, though strong, it succumbs to a still stronger counter-force. Case 2β. Substance changes more readily than forms—for a new substance, the old forms! The sensations P, Q, R . . . are disjoined with difficulty, whether because the force X that unites them is the stronger, or because, though weak, it does not meet any considerable counter-force.

The sensations P, Q, R . . . may originate in certain things and later on appear to the individual as abstractions of those things, such as principles, maxims, precepts, and the like. They constitute an aggregate, a group. The permanence of that aggregate, that group, will be the subject of long and important investigations on our part.1

173. A superficial observer might confuse the Case 2β with Case 1 (§ 172). But in reality they differ radically. Peoples called conservative may be such now only with respect to forms (Case 2β), now only with respect to substance (Case 1). Peoples called formalist may now preserve both forms and substance (Case 1), now only forms (Case 2β). Peoples commonly said to have "fossilized in a certain state" correspond to Case 1.

174. When the unifying force, X, is quite considerable, and the force Y—the trend toward innovation—is very weak or non-existent, we get the phenomena of instinct in animals, and something like the situation in Sparta, a state crystallized in its institutions. When X is strong, but Y equally strong, and innovations are wrought upon substance with due regard to forms, we get a situation like that in ancient Rome—the effort is to change institutions, but disturbing the associations P, Q, R . . . as little as possible. That can be done by allowing the relations P, Q, R . . . to subsist in form. From that point of view, the Roman people may be called formalist at a certain period in its history, and the same may hold for the English. The aversion of those two peoples to disturbing the formal relations P, Q, R . . . may even tempt one to call them conservative. But if we fix our attention on substance, we see that they do not preserve but transform it. Among the ancient Athenians and the modern French, X is relatively feeble. It is difficult to assert that Y was more vigorous among the Athenians than among the Romans, more vigorous among the French than among the English from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. If the effects in question manifest themselves in different ways, the difference lies in the strength of X rather than in the strength of Y.

Let us assume that in the case of two peoples Y is identical in both and X different in both. To bring about innovations, the people among whom X is feeble wipes out the relations P, Q, R . . . and replaces them with other relations. The people among whom X is strong allows those relations to subsist as far as possible and modifies the significance of P, Q, R. . . . Furthermore, there will be fewer "relics from the past" in the first people than in the second. Since X is feeble, there is nothing to hinder abolition of the relations P, Q, R . . . now considered useless; but when X is strong, those relations will be preserved even if they are considered useless.

These inductions are obtainable by observing manifestations of the psychic state A. As regards Rome we have facts in abundance—to begin with, religion. There is now no doubt: (1) that the earliest Romans had no mythology, or at best an exceedingly meagre one; (2) that the classical mythology of the Romans was nothing but a Greek form given to the Roman gods, if not an actual naturalization of foreign deities. Ancient Roman religion consisted essentially of an association of certain religious practices with the conduct of life—it was the perfect type of the P, Q, R . . . associations. Cicero could well say1 that "the whole religion of the Roman people comes down to cult and auspices (§ 361), with a supplement of prophecies originating in portents and prodigies as interpreted by the Sibyl and the haruspices."

175. Even in our day numerous and most variegated types of the associations P, Q, R . . . are observable. In his Au pays des Veddas, pp. 159-62, Deschamps says that in Ceylon "the astrologer plays a part in every act of the native's life. Nothing could be undertaken without his counsel; and . . . I have often seen myself refused the simplest favours because the astrologer had not been consulted as to the day and hour auspicious for granting them." When a piece of ground is to be cleared or brought under cultivation, the astrologer is first consulted, receiving offerings of betel leaves and betel nuts.1 "If the forecast is favourable, gifts of the leaves and nuts are repeated on a specified day, and an 'auspicious hour' (nàkata) is chosen for cutting the first trees and bushes. On the appointed day, the cultivators of the plot selected partake of a repast of cakes, and rice and milk, prepared for the occasion. Then they go forth, their faces turned in the direction designated as propitious by the astrologer. If a lizard chirps at the moment of their departure or if they encounter along the way something of evil omen—a person carrying dead wood or dangerous weapons, a 'rat-snake' crossing the path, a woodpecker—they give up the idea of clearing that particular piece of land, or, more likely, the idea of visiting it that day, picking another nàkata and starting over again. On the other hand, if good omens—a milch cow, a woman nursing a child—are encountered, they proceed cheerily and in all confidence. Once on the ground, an auspicious moment is awaited, then the trees and brush are set on fire. Two or three weeks are allowed for the ground to cool, then another nàkata is set for the final clearing of the land. . . . On a nàkata designated by the same astrologer, a man sows a first handful of rice as a prelude." Birds and also rain may play havoc with the seeding. "To avert such mishaps a kéma or magic brew called navanilla (nine-herbs?) is made ready. . . . If the kéma proves ineffectual, a special kind of oil is distilled for another charm. . . . At weeding-time a nàkata is sought of the same fortune-teller. When the rice-blossoms have faded the ceremony of sprinkling with five kinds of milk takes place." They go on in the same way for each of the successive operations till the rice is finally harvested and barned.2

176. Similar practices are observable to greater or lesser extents in the primitive periods of all peoples.1 Differences are quantitative not qualitative. Preller2 observes that in Rome parallel with the world of the gods was a family of spirits and genii: "Everything that happened in nature, everything that was done by human beings from birth to death, all the vicissitudes of human life and activity, all mutual relationships between citizens, all enterprises . . . were under the jurisdiction of these little gods. Indeed they owe their existence to nothing but those thousands of social relationships with which they are to be identified."3 Originally they were mere associations of ideas, such as we find in fetishism. They constituted groups, and the groups were called divinities or something else of the sort. Pliny soundly remarks that the god population was larger than the population of men.4 When the tendency to give a coating of logic to non-logical conduct developed, people tried to explain why certain acts were associated with certain other acts. It was then that the rites of the cult were referred to great numbers of gods, or taken as manifestations of a worship of natural forces or abstractions. In reality we have the same situation here as in § 175. The psychic state of the Romans A (Figure 2) gave rise, through certain associations of ideas and acts, to the rites B. Later on, or even simultaneously in some instances, the same psychic state expressed itself through the worship C of abstractions, natural forces, attributes of certain divinities, and so on. Then, from the simultaneous existence of B and C came the inference, in most cases mistaken, that B was a consequence of C.

177. The view that acts of cult are consequences of a worship of abstractions, whether considered as "natural forces" or otherwise, is the least acceptable of all and must be absolutely rejected (§§ 158, 996).1 Proofs without end go to show that human beings in general proceed from the concrete to the abstract, and not from the abstract to the concrete. The capacity for abstraction develops with civilization; it is very rudimentary among primitive peoples. Theories that assume it as fully developed in the early stages of human society fall under grave suspicion of error. The ancient Romans, a people still uncivilized, could not have had a very highly developed capacity for abstraction, as would have been necessary if they were to perceive in every concrete fact, sometimes an altogether insignificant fact, a manifestation of some natural power.

Had such a capacity for abstraction existed, it would have left some trace in language. In the beginning, probably, the Greeks did not possess it in any higher degree than the Romans. But they soon acquired it and brought it to remarkable development; and abstraction has left a very definite imprint on their language. Using the article, they are able to turn an adjective, a participle, a whole sentence, into a substantive. The Latins had no article. They could not have availed themselves of that device. But they would certainly have found some other had they felt the need of doing so. On the contrary, it is well known that the capacity for using adjectives substantively is more limited in Latin than in Greek or even in French.2

Probably there is some exaggeration in what St. Augustine says as to the multitude of Roman "gods"; but making all due allowances for overstatement, there are still plenty left who seem to have been created for the sole purpose of accounting logically for the association of certain acts with certain other acts.3

St. Augustine, loc. cit., says that Varro, speaking of the conception of man, gives a list of the gods. He begins with Janus; and, reviewing in succession all the divinities that take care of a man, step by step, down to his extreme old age, he closes with the goddess Nenia, who is naught but the mournful litany chanted at funerals of the aged. He enumerates furthermore divinities who were not concerned with a man's person directly, but rather with the things he uses, such as food, clothing, and the like.

178. Gaston Boissier says in this connexion:1 "What first strikes one is the little life there is in these gods. No one has gone to the trouble of making legends about them. They have no history. All that is known of them is that they have to be worshipped at a given moment and that, at that time, they can be of use. The moment gone, they are forgotten. They do not have real names. The names they are given do not designate them in themselves, but merely the functions which they fulfil."

The facts are exact, the statement of them slightly erroneous, because Boissier is considering them from the standpoint of logical conduct. Not only did the gods in question have very little life—they had none at all. Once upon a time they were mere associations of acts and ideas. Only at a date relatively recent did they get to be gods (§ 995). "All that is known of them" is the little that need be known for such associations of acts and ideas. When it is said that they have to be "worshipped" at certain moments, a new name is being given to an old concept. One might better say that they were "invoked"; or better yet, that certain words were brought into play. When a person pronounces the number 2 (§ 182) to keep a scorpion from stinging, will anybody claim that he is worshipping the number 2 or invoking it? Are we to be surprised that the number 2 has no legend, no history?

179. In the Odyssey, X, vv. 304-05, Hermes gives Ulysses a plant to protect him from the enchantments of Circe—"black at the root, like milk in the flower. The gods call it moly. Difficult it is for mortals to tear from the ground, but the gods can do all things."

Here we have a non-logical action of the pure type. There can be no question of an operation in magic whereby a god is constrained to act. To the contrary, a god gives the plant to a mortal. No reason is adduced to explain the working of the plant. Now let us imagine that we were dealing not with a poetic fiction but with a real plant used for a real purpose. An association of ideas would arise between the plant and Hermes, and no end of logical explanations would be devised for it. The plant would be regarded as a means for constraining Hermes to action—and that really would be magic—or as a means of invoking Hermes, or as a form of Hermes or one of his names, or as a means of paying homage to "forces of nature." Homer designates the plant by the words φάρμακον ἐσθλόν, which might be translated "healing remedy." Is it not evident, one might argue, that there is a resort to natural forces to counteract the pernicious effects of a poison? And so on to all the rank tanglewood of notions that might be read into Homer's story!1

180. The human being has such a weakness for adding logical developments to non-logical behaviour that anything can serve as an excuse for him to turn to that favourite occupation. Associations of ideas and acts were probably as abundant at one time in Greece as they were in Rome; but in Greece most of them disappeared, and sooner than was the case in Rome. Greek anthropomorphism transformed simple associations of ideas and acts into attributes of gods.

Says Boissier:1 "Other countries no doubt felt the need of putting the principal acts of life under divine protection, but ordinarily for such purposes gods well known, powerful, tried and tested of long experience, were chosen, that there might be no doubt as to their efficacy. In Greece the great Athena or the wise Hermes was called upon that a child might grow up competent and wise. In Rome there was a preference for special gods, created for particular purposes and used for no others." The facts are exact, but the explanation is altogether wrong, and again because Boissier is working from the standpoint of logical conduct. His explanation is like an explanation one might make of the declensions in Latin grammar: "Other countries no doubt felt the need of distinguishing the functions of substantive and adjective in a sentence, but ordinarily they chose prepositions for that purpose." No, peoples did not choose their gods, any more than they chose the grammatical forms of their languages. The Athenians never came to any decision in the matter of placing their children under the protection of Hermes and Athena, any more than the Romans after mature reflection chose Vaticanus, Fabulinus, Educa, and Potina for that purpose.

181. It may be that what we see in Greece is merely a stage, somewhat more advanced than the one we find in Rome, in the evolution from the concrete to the abstract, from the non-logical to the logical. It may also be that the evolution was different in the two countries. That point we cannot determine with certainty for lack of documents. In any event—and that is the important thing for the study in which we are engaged—the stages of evolution in Greece and in Rome in historical times were different.

182. In virtue of a most interesting persistence of associations of ideas and acts, words seem to possess some mysterious power over things.1 Even as late as the day of Pliny the Naturalist, one could still write:2 "With regard to remedies derived from human beings there is a very important question that remains unsettled: Do magic words, charms, and incantations have any power? If so, it has to be ascribed to the human being. Individually, one by one, our wisest minds have no faith in such things; but in the mass, in their everyday lives, people believe in them unconsciously.3 [Pliny is an excellent observer here, describing a non-logical action beautifully.] In truth it seems to do no good to sacrifice victims and impossible properly to consult the gods without chants of prayer.4 The words that are used, moreover, are of different kinds, some serving for entreaty, others for averting evil, others for commendation.5 We see that our supreme magistrates pray with specified words. And in order that no word be omitted or uttered out of its proper place, a prompter accompanies from the ritual, another person repeats the words, another preserves 'silence,' and a flutist plays so that nothing else may be heard. The two following facts are deservedly memorable. Whenever a prayer has been interrupted by an invocation or been badly recited, forthwith, without hands being laid to the victim, the top of the liver, or else the heart, has been found either missing or double. Still extant, as a revered example, is the formula with which the Decii, father and son, uttered their vows,6 and we have the prayer uttered by the Vestal Tuccia when, accused of incest, she carried water in a sieve, in the Roman year 609. A man and a woman from Greece, or from some other country with which we were at war, were once buried alive in the Forum Boarium, and such a thing has been seen even in our time. If one but read the sacred prayer that the head of the College of the Quindecemviri is wont to recite ["on such occasions"—Bostock-Riley], one will bear witness to the power of the prayer as demonstrated by the eight hundred and thirty years of our continued prosperity [Bostock-Riley: "by the experience of eight hundred"]. We believe in our day that with a certain prayer our Vestals can arrest the flight of fugitive slaves who have not yet crossed the boundaries of Rome. Once that is granted, once we concede that the gods answer certain prayers or allow themselves to be moved by such words, we have to grant all the rest."7

Going on, loc. cit., 5(3), Pliny appeals to conscience, not to reason, that is, he emphasizes, and very soundly, the non-logical character of the acts in question: "I would appeal, too, for confirmation on this subject, to the intimate experience of the individual [Bostock-Riley translation]. . . . Why do we wish each other a happy new year on the first day of each year? Why do we select men with propitious names to lead the victims in public sacrifices? . . . Why do we believe that odd numbers are more effective than others8—a thing [Bostock-Riley] that is particularly observed with reference to the critical days in fever. . . . Attalus [Philometor] avers that if one pronounces the number duo9 at sight of a scorpion, the scorpion stops and does not sting."10

183. These actions, in which words act upon things, belong to that class of operations which ordinary language more or less vaguely designates as magic. In the extreme type, certain words or acts, by some unknown virtue, have the power to produce certain effects. Next a first coating of logic explains that power as due to the interposition of higher beings, of deities. Going on in that direction we finally get to another extreme where the action is logical throughout—the mediaeval belief, for instance, that by selling his soul to the Devil a human being could acquire the power to harm people. When a person interested strictly in logical actions happens on phenomena of the kind just mentioned, he looks at them contemptuously as pathological states of mind, and goes his way without further thought of them. But anyone aware of the important part non-logical behaviour plays in human society must examine them with great care.1

184. Let us suppose that the only cases known to us showed that success in operations in magic depended on the activity of the Devil. Then we might accept the logical interpretation and say, "Men believe in the efficacy of magic because they believe in the Devil." That inference would not be substantially modified by our discovery of other cases where some other divinity functioned in place of the Devil. But it collapses the moment we meet cases that are absolutely independent of any sort of divine collaboration whatsoever. It is then apparent that the essential element in such phenomena is the non-logical action that associates certain words, invocations, practices, with certain desired effects; and that the presence of gods, demons, spirits, and so on is nothing but a logical form that is given to those associations.1

The substance remaining intact, several forms may coexist in one individual without his knowing just what share belongs to each. The witch in Theocritus, Idyllia, II, vv. 14-17, relies both upon the contributions of gods and upon the efficacy of magic, without distinguishing very clearly just how the two powers are to function. She beseeches Hecate to make the philtres she is preparing deadlier than the potions of Circe, or Medea, or the golden-haired Perimede. Had she relied on Hecate alone, it would have been simpler for her to ask the goddess directly for results that she hoped to get from the philtres. When she repeats the refrain "Wry-neck, wry-neck (ἰνγή, a magic bird), drag this man to my dwelling!" she is evidently envisaging some occult relationship between the bird and the effect she desires.2

For countless ages people have believed in such nonsense in one form or another; and there are some who take such things seriously even in our day. Only, for the past two or three hundred years there has been an increase in the number of people who laugh at them as Lucian did. But the vogue of spiritualism, telepathy, Christian Science (§ 16952), and what not, is enough to show what enormous power these sentiments and others like them still have today.3

185. "Your ox would not die unless you had an evil neighbour," says Hesiod (Opera et dies, v. 348); but he does not explain how that all happens. The Laws of the XII Tables deal with the "man who shall bewitch the crops"1 and with the "man who shall chant a curse" without explaining exactly what was involved in those operations. That type of non-logical action has also come down across the ages and is met with in our day in the use of amulets. In the country about Naples hosts of people wear coral horns on their watch-chains to ward off the evil eye. Many gamblers carry amulets and go through certain motions considered helpful to winning.2

186. Suppose we confine ourselves to just one of these countless non-logical actions—to rites relating to the causation or prevention of storms, and to the destruction or protection of crops. And to avoid any bewilderment resulting from examples chosen at random here and there and brought together artificially, suppose we ignore anything pertaining to countries foreign to the Graeco-Roman world. That will enable us to keep to one phenomenon in its ramifications in our Western countries, with some very few allusions to data more remotely sought.1 The method we adopt for the group of facts we are about to study is the method that will serve for other similar groups of facts. The various phenomena in the group constitute a natural family, in the same sense that the Papilionaceae in botany constitute a natural family: they can readily be identified and grouped together. There are huge numbers of them. We cannot possibly mention them all, but we can consider at least their principal types.

187. We get many cases where there is a belief that by means of certain rites and practices it is possible to raise or quell a storm. At times it is not stated just how the effect ensues—it is taken as a datum of fact. At other times, the supposed reasons are given; the effect is taken as the theoretically explainable consequence of the working of certain forces. In general terms, meteorological phenomena are considered dependent upon certain rites and practices, either directly, or else indirectly, through the interposition of higher powers.

188. Palladius gives precepts without comment. Columella adds a touch of logical interpretation, saying that custom and experience have shown their efficacy.1 Long before their time, Empedocles, according to Diogenes Laertius, Empedocles, VIII, 2, 59 (Hicks, Vol. II, pp. 373-75), boasted that he had power over the rain and the winds. On one occasion when the winds were blowing hard and threatening to destroy the harvests, he had bags of ass's skin made and placed on the mountains and in that way, trapped in the bags, the winds abated (loc. cit., 60, quoting Timaeus). Suidas makes this interpretation a little less absurd by saying that Empedocles stretched asses' skins about the city. Plutarch, Adversus Colotem, 32 (Goodwin, Vol. V, p. 381), gives an explanation still less implausible (though implausible enough) by having Empedocles save a town from plague and crop-failure by stopping up the mountain gorges through which a wind swept down over the plain. In another place, De curiositate, 1 (Goodwin, Vol. II, p. 424), he repeats virtually the same story, but this time mentioning only the plague. Clement of Alexandria credits Empedocles with calming a wind that was bringing disease to the inhabitants and causing barrenness in the women—and in that a new element creeps in, for the feat would be a Greek counterfeit of a Judaic miracle; and so we get a theological interpretation.2

189. It is evident that here we have, as it were, a tree-trunk with many branches shooting off from it: a constant element, then a multitude of interpretations. The trunk, the constant element, is the belief that Empedocles saved a town from damage by winds; the ramifications, the interpretations, are the various conceptions of the way in which that result was achieved, and naturally they depend upon the temperaments of the writers advancing them: the practical man looks for a pseudo-experimental explanation; the theologian, for a theological explanation.

In Pausanias we get a conglomerate of pseudo-experimental, magical, and theological explanations. Speaking of a statue of Athena Anemotis erected at Motona, Pausanias writes, Periegesis, IV, Messenia, 35, 8: "It is said that Diomedes erected the statue and gave the goddess her name. Winds very violent and blowing out of season began devastating the country. Diomedes offered prayers to Athena; whereafter the country suffered no further ravages from the winds." Ibid., II, Corinth, 12, 1: "At the foot of the hill (for the temple is built on a hill) stands the Altar of the Winds, whereon, one night each year, the priest sacrifices to the winds. In four pits that are there he performs other secret ceremonies to calm the fury of the winds, and likewise chants magic words that are said to come down from Medea." Ibid., 34: "I record this fact also, whereat I marvelled greatly while among the Methanians. If the south-east wind ["the Lipz"] blows in from the Saronic Gulf when the vines are budding, it dries up the buds. So, as soon as the wind begins to blow, two men take a white-feathered cock, tear it in two, and run around the vineyards in opposite directions, each carrying half of the cock. Coming back to the point at which they started, they bury it. Such the remedy they have devised against that wind."

Pomponius Mela mentions nine virgins who dwelt on the "Isle of Sena" and who were able to stir up the winds and the sea with their chants.1 In the Geoponicon, compiled by Cassianus Bassus, I, 14, several methods of saving the fields from hail are mentioned; but the compiler of that collection explains that he has transcribed them only to avoid seeming disrespectful to things that have come down from the forefathers. His own beliefs, in a word, are different.

190. One branch shooting off from this nucleus of interpretation overlying non-logical behaviour ends in a deification of tempests. Cicero, De natura deorum, III, 20, 51, has Cotta meet Balbus with the objection that if the sky, the stars, and the phenomena of weather were to be deified the number of the gods would be absurdly great. In this case the deification stands by itself; in other examples, it bifurcates and gives rise to numerous interpretations, personifications, explanations.1

191. Capacity for controlling winds and storms becomes a sign of intellectual or spiritual power, as in Empedocles; or even of divinity, as in Christ quelling the tempest.1 Magicians and witches demonstrate their powers in that fashion; and Greek anthropomorphism knows lords of winds, storms, and the sea.

192. Sacrifices were made to the winds. The sacrifice is just a logical development of a magical operation like the use of the white cock just described. In fact for that ceremony to become a sacrifice, it need simply be stated that the cock is torn in twain as a sacrifice to this or that divinity.

Virgil has a black sheep sacrificed to the Tempest, a white sheep to the fair Zephyr. Note the elements in his action: 1. Principal element: the notion that it is possible to influence the winds by means of certain acts. 2. Secondary element: logical explanation of such acts, by introducing an imaginary being (personified winds, divinities, and the like). 3. An element still more secondary: specification of the acts, through certain similarities between black sheep and storms, white sheep and fair winds.1

193. The winds protected the Greeks against the Persian invasion and in gratitude the Delphians reared an altar to them at Pthios.1 It is a familiar fact that Boreas, son-in-law to the Athenians by virtue of his marriage to Orithyia, daughter of Erechtheus, dispersed the Persian fleet, and therefore well deserved the altar that the Athenians reared in his honour on the shores of the Ilissus.2

Boreas, good fellow, looked after other people besides the Athenians. He destroyed the fleet of Dionysius, as the latter was voyaging to attack the Thurii (Tarentines). "The Thurii therefore sacrificed to Boreas and elected that wind to citizenship [in their city]; assigned him a house and a piece of land, and each year celebrated a festival in his honour."3 He also saved the Megalopolitanians when they were besieged by the Spartans; and for that reason they offered sacrifices to him every year and honoured him as punctiliously as any other god.4

The art of lulling the winds was known to the Persian Magi also. Herodotus relates, Historiae, VII, 191, in connexion with the tempest that Boreas raised to help the Athenians and which inflicted heavy losses on the Persian fleet: "For three days the storm raged. The Magi sacrificed victims and addressed magical incantations to the wind, and sacrificed further to Thetis and the Nereids. Whereupon the winds ceased on the fourth day—unless it be that they fell of their own accord." Interesting this scepticism on the part of Herodotus!5

194. The notion that winds, rains, tempests, can be produced by art of magic is a common one in ancient writers.1 Seneca discusses the causes of weather at length and derides magic. He does not admit the possibility of forecasting the weather by observation, regarding observation as just a preparation for the rites commonly performed for averting storms.2 He says that at Cleonae there were public officials known as "hail-observers." As soon as they gave warning of the approach of a storm, the inhabitants rushed to the temple and sacrificed some a ewe, others a fowl. Those who had nothing to sacrifice pricked a finger and shed a little blood, and the clouds moved on in another direction. "People have wondered how that happens. Some, as befits educated people, deny that it is possible to bargain with hail-stones and ransom oneself from storms by trifling gifts, granted that gifts sway even the gods. Others suspect that the blood may contain some property that is able to banish clouds. But how can so little blood contain a force of such magnitude as to work far up in the skies and be felt by clouds? How much simpler to say that it is stuff and nonsense. All the same the officials entrusted with forecasting storms at Cleonae were punished when through oversight on their part the vines and the crops were damaged. Our own XII Tables forbid anyone's laying an enchantment on another's crops. An ignorant antiquity believed that clouds could be compelled or dispelled by magic. But such things are so manifestly impossible that no great schooling is required to know as much."

Few writers, however, evince the scepticism of Seneca, and we have a long series of legends about storms and winds that come down to a day very close to our own.

195. The Roman legions led by Marcus Aurelius against the Quadi chanced to be caught by a shortage of water, but a storm came along just in time to save them. The fact seems to be well authenticated.1 So then, the why and wherefore of the storm has to be explained; and everybody does so according to his individual sentiments and inclinations.

It may be a case of witchcraft. Even the name of the magician is known—in such cases one can be very specific at small cost! Suidas says he was one Arnuphis, "an Egyptian philosopher who, being in attendance on Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher, Emperor of the Romans, at the time when the Romans fell short of water, straightway caused black clouds to gather in the skies and a heavy rain to fall, wherewith thunder and frequent lightning; and those things he did of his science. Others say that the prodigy was the work of Julian the Chaldean."2

Then again pagan gods may have a hand in it—otherwise what are gods good for? Dio Cassius, Historia Romana, LXXII, 8 (Cary, Vol. IX, pp. 27-29), says that while the Romans were hard pressed by the Quadi and were suffering terribly from heat and thirst, "of a sudden many clouds gathered and much rain fell, not without divine purpose, and violently. And it is said of this that an Egyptian magician, Arnuphis by name, who was with Marcus, invoked a number of divinities3 by magic art, and chiefly Hermes Aërius, and so brought on the rain."

Claudian believes that the enemy was put to flight by a rain of fire. And the cause? Magic, or else benevolence of Jove the Thunderer.4 Capitolinus knows that Marcus Antoninus "with his prayers turned the thunderbolts of heaven against the war machines of the enemy and obtained rain for his soldiers who were suffering from thirst.5 With Lampridius the episode is further elaborated and assumes new garb. Marcus Antoninus has succeeded in making the Marcomanni friendly to the Romans by certain magical practices. The formulas are withheld from Elagabalus in fear lest he be desiring to start a new war.6

Finally the Christians claim the miracle for their God. On the passage from Dio Cassius (LXXII, 8) quoted above, Xiphilinus (Cary, Dio, Vol. IX, pp. 29-33) notes that Dio wittingly or unwittingly, but he suspects wittingly, misleads the reader. He surely knew—since he mentions it himself—all about the "Thundering Legion," the Fulminata, to which, and not to the magician Arnuphis, the rescue of the army was due! The truth is as follows: Marcus had a legion made up entirely of Christians. During the battle, the praetor's adjutant came and told Marcus that there was nothing which Christians were unable to obtain by prayer and that there was a legion of Christians in the army. "Hearing which, Marcus urged them to bestir themselves and pray to their God. They prayed, and God heard their prayer immediately and smote the enemy with lightning, whereas the Romans He comforted with rain." Xiphilinus adds that a letter of Marcus Aurelius on the incident was said to be in existence in his time. The letter, forged by people more distinguished for piety than veracity, is also alluded to by other writers; and Justin Martyr goes so far as to give its authentic text.7

196. So the legend expands, widening in scope and gradually approximating a veritable novel. But not only the external embellishments increase in number. Concepts multiply in the substance itself. The nucleus is a mechanical concept.1 Certain words are uttered, certain rites are performed, and the rain falls. Then comes a feeling that that has to be explained. A first theory assumes the interposition of supernatural beings. But then the interference of such gods has also to be explained, and we get a second explanation. But that explanation too bifurcates according to the supposed reasons for the intervention, foremost among which stands the ethical reason, so introducing a new concept that was altogether absent in the magical operation proper. This new concept enlarges the scope of the whole procedure. Rain was once the sole objective of the rite. Now it becomes a means whereby the divine power rewards its favourites and punishes their enemies, and then, further, a means for rewarding faith and virtue. A final step is to move on from the particular case to the general. It is no longer a question of a single fact, but of a multiplicity of facts, all following a certain rule. This leap is taken by Tertullian. After telling the story of the rain secured by the soldiers of Marcus Aurelius, he adds: "How often have droughts not been stopped by our prayers and our fasts!"2

Other cases of the same kind could be adduced; which goes to show that the sentiments in which they originate are fairly common throughout the human race.3

197. In Christian writers it is natural that logical explanations of the general law of storms should centre about the Devil. Clement of Alexandria records the belief that wicked angels have a hand in tempests and other such calamities (§ 1882).1 But, let us not forget, that is just an adjunct, by way of explanation, to the basic element— the belief that it is possible to influence storms and other calamities of the kind by certain rites. Victorious Christianity had to fight for its interpretations first with ancient pagan practices and later on with magical arts that in part continued the pagan and in part were new. But great the need of escaping storms! And powerful the thought that there were ways of doing so! So in one manner or another the need was covered and the thought carried out.2

198. In mediaeval times individuals endowed with such powers were known as tempestarii, and even the law took cognizance of them. Nevertheless the Church did not recognize this power of producing storms without a struggle. The Council of Braga in the year 563 (Labbe, Vol. VI, p. 518) anathematizes anyone teaching that the Devil can produce thunder, lightning, tempests, or drought. A celebrated ecclesiastical decree denies all basis in fact to fanciful tales about witches.1

St. Agobard wrote an entire book "against idiotic notions current as to hail and thunder." Says he: "In these parts nearly all people, noble or villein, burgher or rustic, old or young, believe that hail and thunder can be produced at the will of men. They therefore exclaim at the first signs of thunder and lightning: 'Raised air!' Asked to explain what 'raised air' is, they will tell you, some shamefacedly as though conscious of sin, others with the wonted frankness of the ignorant, that the air has been stirred by the incantations of individuals known as 'tempestuaries' and that that is why they say 'raised air.' We have seen and heard many people possessed of such stupidity and out of their heads with such lunacy as to believe and say that there is a certain country called 'Magonie' whence ships sail out on the clouds and return laden with the grain which the hail mows and the storms blow down, and that the 'tempestuaries' are paid by such aerial mariners for the grain and other produce delivered to them. We have seen a great crowd of people—blinded by such great stupidity as to believe such things possible—drag four persons in chains before our court, three men and a woman, alleging that they had fallen from one of those ships. They had been held in chains for several days till the court convened; then they were produced, in our presence, as I said, as culprits worthy to be stoned to death. Nevertheless, after much parley the truth prevailing, the accusers were, in the prophet's words, confounded like thieves caught in the act."2

St. Agobard demonstrates from Holy Writ the error of believing that hail and thunder are at the beck and call of human beings. Others, on the contrary, will likewise show by Scripture that the belief is sound. Yes and no have at all times been produced from Scripture with equal readiness.

199. Doctrines recognizing the powers of witches were mistrusted by the Church for two reasons, at first because they looked like survivals of paganism, the gods of which were identified with devils; then because they were tainted with Manicheism, setting up a principle of evil against a principle of good. But owing to the pressure of the popular beliefs in which the non-logical impulses involved in magic expressed themselves, the Church finally yielded to something it could not prevent, and with little trouble found an interpretation humouring popular superstition and at the same time not incompatible with Catholic theology. After all, what did it want? It wanted the principle of evil to be subordinate to the principle of good. No sooner said than done! We can grant, to be sure, that magic is the work of the Devil—but we will add, "God permitting." That will remain the final doctrine of the Catholic Church.

200. Popular superstitions exerted pressure not only upon the Church but also upon secular governments; and they, without bothering very much to find logical interpretations, set out with a will to punish all sorts of sorcerers and witches, "tempestuaries" included.1

201. Whenever a certain state of fact, a certain state of belief, exists, there is always someone on hand to try to take advantage of it; and it is therefore not surprising that Church, State, and individuals should all have tried to profit by the belief in witchcraft. St. Agobard reports that blackmail was paid to "tempestuaries,"1 and Charlemagne, no less, admonishes his subjects to pay their tithes to the Church regularly if they would be surer of their crops.2

202. In the Middle Ages and the centuries following there was a veritable deluge of accusations against sorcerers for stirring up storms and destroying harvests. Humanity lived in terror of the Devil for generation after generation. Whenever people spoke of him, they seemed to go out of their heads, and, as might be expected of raving lunatics, spread death and ruin recklessly about.

203. The Malleus maleficarum (Hammer for Witches) of Sprenger and Kramer gives a good summary of the doctrine prevailing in the fifteenth century, though it was also the doctrine of periods earlier and later: