1. Human society is the subject of many researches. Some of them constitute specialized disciplines: law, political economy, political history, the history of religions, and the like. Others have not yet been distinguished by special names. To the synthesis of them all, which aims at studying human society in general, we may give the name of sociology.

2. That definition is very inadequate. It may perhaps be improved upon—but not much; for, after all, of none of the sciences, not even of the several mathematical sciences, have we strict definitions. Nor can we have. Only for purposes of convenience do we divide the subject-matter of our knowledge into various parts, and such divisions are artificial and change in course of time. Who can mark the boundaries between chemistry and physics, or between physics and mechanics? And what are we to do with thermodynamics? If we locate that science in physics, it will fit not badly there; if we put it with mechanics, it will not seem out of place; if we prefer to make a separate science of it, no one surely can find fault with us. Instead of wasting time trying to discover the best classification for it, it will be the wiser part to examine the facts with which it deals. Let us put names aside and consider things.

In the same way, we have something better to do than to waste our time deciding whether sociology is or is not an independent science—whether it is anything but the "philosophy of history" under a different name; or to debate at any great length the methods to be followed in the study of sociology. Let us keep to our quest for the relationships between social facts, and people may then give to that inquiry any name they please. And let knowledge of such relationships be obtained by any method that will serve. We are interested in the end, and much less or not at all interested in the means by which we attain it.

3. In considering the definition of sociology just above we found it necessary to hint at one or two norms that we intend to follow in these volumes. We might do the same in other connexions as occasion arises. On the other hand, we might very well set forth our norms once and for all. Each of those procedures has its merits and its defects. Here we prefer to follow the second.1

4. The principles that a writer chooses to follow may be put forward in two different ways. He may, in the first place, ask that his principles be accepted as demonstrated truths. If they are so accepted, all their logical implications must also be regarded as proved. On the other hand, he may state his principles as mere indications of one course that may be followed among the many possible. In that case any logical implication which they may contain is in no sense demonstrated in the concrete, but is merely hypothetical—hypothetical in the same manner and to the same degree as the premises from which it has been derived. It will therefore often be necessary to abstain from drawing such inferences: the deductive aspects of the subject will be ignored, and relationships be inferred from the facts directly.

Let us consider an example. Suppose Euclid's postulate that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points is set before us as a theorem. We must give battle on the theorem; for if we concede it, the whole system of Euclidean geometry stands demonstrated, and we have nothing left to set against it. But suppose, on the contrary, the postulate be put forward as a hypothesis. We are no longer called upon to contest it. Let the mathematician develop the logical consequences that follow from it. If they are in accord with the concrete, we will accept them; if they seem not to be in such accord, we will reject them. Our freedom of choice has not been fettered by any anticipatory concession. Considering things from that point of view, other geometries—non-Euclidean geometries—are possible, and we may study them without in the least surrendering our freedom of choice in the concrete.

If before proceeding with their researches mathematicians had insisted upon deciding whether or not the postulate of Euclid corresponded to concrete reality, geometry would not exist even today. And that observation is of general bearing. All sciences have advanced when, instead of quarrelling over first principles, people have considered results. The science of celestial mechanics developed as a result of the hypothesis of the law of universal gravitation. Today we suspect that that attraction may be something different from what it was once thought to be; but even if, in the light of new and better observations of fact, our doubts should prove well founded, the results attained by celestial mechanics on the whole would still stand. They would simply have to be retouched and supplemented.

5. Profiting by such experience, we are here setting out to apply to the study of sociology the methods that have proved so useful in the other sciences. We do not posit any dogma as a premise to our research; and our statement of principles serves merely as an indication of that course, among the many courses that might be chosen, which we elect to follow. Therefore anyone who joins us along such a course by no means renounces his right to follow some other. From the first pages of a treatise on geometry it is the part of the mathematician to make clear whether he is expounding the geometry of Euclid, or, let us say, the geometry of Lobachevski. But that is just a hint; and if he goes on and expounds the geometry of Lobachevski, it does not follow that he rejects all other geometries. In that sense and in no other should the statement of principles which we are here making be taken.

6. Hitherto sociology has nearly always been expounded dogmatically. Let us not be deceived by the word "positive" that Comte foisted upon his philosophy. His sociology is as dogmatic as Bossuet's Discourse on Universal History. It is a case of two different religions, but of religions nevertheless; and religions of the same sort are to be seen in the writings of Spencer, De Greef, Letourneau, and numberless other authors.

Faith by its very nature is exclusive. If one believes oneself possessed of the absolute truth, one cannot admit that there are any other truths in the world. So the enthusiastic Christian and the pugnacious free-thinker are, and have to be, equally intolerant. For the believer there is but one good course; all others are bad. The Mohammedan will not take oath upon the Gospels, nor the Christian upon the Koran. But those who have no faith whatever will take their oath upon either Koran or Gospels—or, as a favour to our humanitarians, on the Social Contract of Rousseau; nor even would they scruple to swear on the Decameron of Boccaccio, were it only to see the grimace Senator Berenger would make and the brethren of that gentleman's persuasion.1 We are by no means asserting that sociologies derived from certain dogmatic principles are useless; just as we in no sense deny utility to the geometries of Lobachevski or Riemann. We simply ask of such sociologies that they use premises and reasonings which are as clear and exact as possible. "Humanitarian" sociologies we have to satiety—they are about the only ones that are being published nowadays. Of metaphysical sociologies (with which are to be classed all positive and humanitarian sociologies) we suffer no dearth. Christian, Catholic, and similar sociologies we have to some small extent. Without disparagement of any of those estimable sociologies, we here venture to expound a sociology that is purely experimental, after the fashion of chemistry, physics, and other such sciences.2 In all that follows, therefore, we intend to take only experience3 and observation as our guides. So far as experience is not contrasted with observation, we shall, for love of brevity, refer to experience alone. When we say that a thing is attested "by experience," the reader must add "and by observation." When we speak of "experimental sciences," the reader must supply the adjective "observational," and so on.

7. Current in any given group of people are a number of propositions, descriptive, preceptive, or otherwise. For example: "Youth lacks discretion." "Covet not thy neighbour's goods, nor thy neighbour's wife." "Love thy neighbour as thyself." "Learn to save if you would not one day be in need." Such propositions, combined by logical or pseudo-logical nexuses and amplified with factual narrations1 of various sorts, constitute theories, theologies, cosmogonies, systems of metaphysics, and so on. Viewed from the outside without regard to any intrinsic merit with which they may be credited by faith, all such propositions and theories are experimental facts, and as experimental facts we are here obliged to consider and examine them.

8. That examination is very useful to sociology; for the image of social activity is stamped on the majority of such propositions and theories, and often it is through them alone that we manage to gain some knowledge of the forces which are at work in society—that is, of the tendencies and inclinations of human beings. For that reason we shall study them at great length in the course of these volumes. Propositions and theories have to be classified at the very outset, for classification is a first step that is almost indispensable if one would have an adequate grasp of any great number of differing objects.1 To avoid endless repetition of the words "proposition" and "theory," we shall for the moment use only the latter term; but whatever we say of "theories" should be taken as applying also to "propositions," barring specification to the contrary.

9. For the man who lets himself be guided chiefly by sentiment—for the believer, that is—there are usually but two classes of theories: there are theories that are true and theories that are false. The terms "true" and "false" are left vaguely defined. They are felt rather than explained.

10. Oftentimes three further axioms are present:

1. The axiom that every "honest" man, every "intelligent" human being, must accept "true" propositions and reject "false" ones. The person who fails to do so is either not honest or not rational. Theories, it follows, have an absolute character, independent of the minds that produce or accept them.

2. The axiom that every proposition which is "true" is also "beneficial," and vice versa. When, accordingly, a theory has been shown to be true, the study of it is complete, and it is useless to inquire whether it be beneficial or detrimental.

3. At any rate, it is inadmissible that a theory may be beneficial to certain classes of society and detrimental to others—yet that is an axiom of modern currency, and many people deny it without, however, daring to voice that opinion.

11. Were we to meet those assertions with contrary ones, we too would be reasoning a priori; and, experimentally, both sets of assertions would have the same value—zero. If we would remain within the realm of experience, we need simply determine first of all whether the terms used in the assertions correspond to some experimental reality, and then whether the assertions are or are not corroborated by experimental facts. But in order to do that, we are obliged to admit the possibility of both a positive and a negative answer; for it is evident that if we bar one of those two possibilities a priori, we shall be giving a solution likewise a priori to the problem we have set ourselves, instead of leaving the solution of it to experience as we proposed doing.

12. Let us try therefore to classify theories, using the method we would use were we classifying insects, plants, or rocks. We perceive at once that a theory is not a homogeneous entity, such as the "element" known to chemistry. A theory, rather, is like a rock, which is made up of a number of elements. In a theory one may detect descriptive elements, axiomatic assertions, and functionings of certain entities, now concrete, now abstract, now real, now imaginary; and all such things may be said to constitute the matter of the theory. But there are other things in a theory: there are logical or pseudo-logical arguments, appeals to sentiment, "feelings," traces of religious and ethical beliefs, and so on; and such things may be thought of as constituting the instrumentalities whereby the "matter" mentioned above is utilized in order to rear the structure that we call a theory. Here, already, is one aspect under which theories may be considered. It is sufficient for the moment to have called attention to it.1

13. In the manner just described, the structure has been reared—the theory exists. It is now one of the objects that we are trying to classify. We may consider it under various aspects:

1. Objective aspect. The theory may be considered without reference to the person who has produced it or to the person who assents to it—"objectively," we say, but without attaching any metaphysical sense to the term. In order to take account of all possible combinations that may arise from the character of the matter and the character of the nexus, we must distinguish the following classes and subclasses:

| Class I. | Experimental matter |

| Ia. | Logical nexus |

| Ib. | Non-logical nexus |

| Class II. | Non-experimental matter |

| IIa. | Logical nexus |

| IIb. | Non-logical nexus |

The subclasses Ib and IIb comprise logical sophistries, or specious reasonings calculated to deceive. For the study in which we are engaged they are often far less important than the subclasses Ia or IIa. The subclass Ia comprises all the experimental sciences; we shall call it logico-experimental. Two other varieties may be distinguished in it:

Ia1, comprising the type that is strictly pure, with the matter strictly experimental and the nexus logical. The abstractions and general principles that are used within it are derived exclusively from experience and are subordinated to experience (§ 63).

Ia2, comprising a deviation from the type, which brings us closer to Class II. Explicitly the matter is still experimental, and the nexus logical; but the abstractions, the general principles, acquire (implicitly or explicitly) a significance transcending experience. This variety might be called transitional. Others of like nature might be considered, but they are far less important than this one.

The classification just made, like any other that might be made, is dependent upon the knowledge at our command. A person who regards as experimental certain elements that another person regards as non-experimental will locate in Class I a proposition that the other person will place in Class II. The person who thinks he is using logic and is mistaken will class among logical theories a proposition that a person aware of the error will locate among the nonlogical. The classification above is a classification of types of theories. ln reality, a given theory may be a blend of such types—it may, that is, contain experimental elements and non-experimental elements, logical elements and non-logical elements.1

2. Subjective aspect. Theories may be considered with reference to the persons who produce them and to the persons who assent to them. We shall therefore have to consider them under the following subjective aspects:

a. Causes in view of which a given theory is devised by a given person. Why does a given person assert that A = B? Conversely, if he makes that assertion, why does he do so?

b. Causes in view of which a given person assents to a given theory. Why does a given person assent to the proposition A = B? Conversely, if he gives such assent, why does he do so?

These inquiries are extensible from individuals to society at large.

3. Aspect of utility. In this connexion, is important to keep the theory distinct from the state of mind, the sentiments, that it reflects. Certain individuals evolve a theory because they have certain sentiments; but then the theory reacts in turn upon them, as well as upon other individuals, to produce, intensify, or modify certain sentiments.

| I. | Utility or detriment resulting from the sentiments reflected by a theory: |

| Ia. | As regards the person asserting the theory |

| Ib. | As regards the person assenting to the theory |

| II. | Utility or detriment resulting from a given theory: |

| IIa. | As regards the person asserting the theory |

| IIb. | As regards the person assenting to it. |

These considerations, too, are extensible to society at large.

We may say, then, that we are to consider propositions and theories under their objective and their subjective aspects, and also from the standpoint of their individual or social utility. However, the meanings of such terms must not be derived from their etymology, or from their usage in common parlance, but exclusively in the manner designated later in § 119.

14. To recapitulate: Given the proposition A = B, we must answer the following questions:

1. Objective aspect. Is the proposition in accord with experience, or is it not?

2. Subjective aspect. Why do certain individuals assert that A = B? And why do other individuals believe that A = B?

3. Aspect of utility. What advantage (or disadvantage) do the sentiments reflected by the proposition A = B have for the person who states it, and for the person who accepts it? What advantage (or disadvantage) does the theory itself have for the person who puts it forward, and for the person who accepts it?

In an extreme case the answer to the first question is yes; and then, as regards the other question, one adds: "People say (people believe) that A = B, because it is true." "The sentiments reflected in the proposition are beneficial1 because true." "The theory itself is beneficial because true." In this extreme case, we may find that data of logico-experimental science are present, and then "true" means in accord with experience. But also present may be data that by no means belong to logico-experimental science, and in such event "true" signifies not accord with experience but something else—frequently mere accord with the sentiments of the person defending the thesis. We shall see, as we proceed with our experimental research in chapters hereafter, that the following cases are of frequent occurrence in social matters:

a. Propositions in accord with experience that are asserted and accepted because of their accord with sentiments, the latter being now beneficial, now detrimental, to individuals or society

b. Propositions in accord with experience that are rejected because they are not in accord with sentiments, and which, if accepted, would be detrimental to society

c. Propositions not in accord with experience that are asserted and accepted because of their accord with sentiments, the latter being beneficial, oftentimes exceedingly so, to individuals or society

d. Propositions not in accord with experience that are asserted and accepted because of their accord with sentiments, and which are beneficial to certain individuals, detrimental to others, and now beneficial, now detrimental, to society.

On all that we can know nothing a priori. Experience alone can enlighten us.

15. After objects have been classified, they have to be examined, and to that research we shall devote the next chapters. In Chapters IV and V we shall consider theories with special reference to their accord with experience and observation. In Chapters VI, VII, and VIII we shall study the sentiments in which theories originate. In Chapters IX and X we shall consider the ways in which sentiments are reflected in theories. In Chapter XI we shall examine the characteristics of the elements so detected. And finally in Chapters XII and XIII we shall see the social effects of the various elements, and arrive at an approximate concept of variations in the forms of society—the goal at which we shall have been aiming all along and towards which all our successive chapters will have been leading.1

16. From the objective standpoint (§ 13), we divided propositions or theories into two great classes, the first in no way departing from the realm of experience, the second overstepping it in some respect or other.1 If one would reason at all exactly, it is essential to keep those two classes distinct, for at bottom they are heterogeneous things that must never be in any way confused, and which cannot, either, be compared.2 Each of them has its own manner of reasoning and, in general, its own peculiar standard whereby it falls into two divisions, the one comprising propositions that are in logical accord with the chosen standard and are called true; the other comprising propositions which are not in accord with that standard and are called false. The terms "true" and "false," therefore, stand in strict dependence on the standard chosen. If one should try to give them an absolute meaning, one would be deserting the logico-experimental field for the field of metaphysics.

The standard of truth for propositions of the first class lies in experience and observation only. The standard of truth for the second class lies outside objective experience—in some divine revelation; in concepts that the human mind finds in itself, as some say, without the aid of objective experience; in the universal consensus of mankind, and so on.

There must never be any quarrelling over names. If someone is minded to ascribe a different meaning to the terms "truth" and "science," for our part we shall not raise the slightest objection. We are satisfied if he specifies the sense that he means to give to the terms he uses and especially the standard by which he recognizes a proposition as "true" or "false."

17. If that standard is not specified, it is idle to proceed with a discussion that could only resolve itself into mere talk; just as it would be idle for lawyers to plead their cases in the absence of a judge. If someone asserts that "A has the property B," before going on with the discussion we must know who is to judge the controversy between him and another person who maintains that "A does not have the property B." If it is agreed that the judge shall be objective experience, objective experience will then decide whether A has, or does not have, the property B. Throughout the course of these volumes, we are in the logico-experimental field. I intend to remain absolutely in that field and refuse to depart from it under any inducement whatsoever. If, therefore, the reader desires a judge other than objective experience, he should stop reading this book, just as he would refrain from proceeding with a case before a court to which he objected.

18. If people disposed to argue the propositions mentioned desire a judge other than objective experience, they will do well to declare exactly what their judge is to be, and if possible (it seldom is) to make themselves very clear on the point!. In these volumes we shall refrain from participating in arguments as to the substance of propositions and theories. We are to discuss them strictly from the outside, as social facts with which we have to deal.

19. Metaphysicists generally give the name of "science" to knowledge of the "essences" of things, to knowledge of "principles." If we accept that definition for the moment, it would follow that this" work would be in no way scientific. Not only do we refrain from dealing with essences and principles: we do not even know the meaning of those terms (§ 530).

Vera, Hegel's French translator, says,1 "The notions of science and absolute science are inseparable. . . . Now if there be an absolute science, it is not and cannot be other than philosophy. So philosophy is the common foundation of all the sciences, and as it were the common intelligence of all intelligences." In this book we refuse to have anything whatever to do with such a science, and with those other pretty things that go with it. "The absolute (in other words, essence) and unity (in other words, the necessary relations of beings) are the two prime conditions of science." Both of them will be found missing in these volumes, and we do not even know what they may be. We seek the relationships obtaining between things within the limits of the space and time known to us, and we ask experience and observation to reveal them to us. "Philosophy is at once an explanation and a creation." We have neither the desire nor the ability to explain, in Vera's sense of the term, much less to create. "The science that knows the absolute and grasps the innermost reason of things knows how and why events come to pass and beings are engendered [That is something we do not know.], and not only knows but in a certain way itself engenders and brings to pass in the very fact of grasping the absolute. And indeed we must either deny science, or else admit that there is a point where knowledge and being, thought and its object, coincide and are identified; and a science of the absolute that arose apart from the absolute, and so failed of achieving its real and innermost nature, would not be a science of the absolute, or more exactly, would not be science at all."

20. Well said! In that we agree with Vera. If science is what Vera's terms describe it as being—terms as inspiring as they are (to us) incomprehensible—we are not here dealing with science. We are, however, dealing with another thing that Vera very well describes in a particular case when he says, p. 214, note: "Generally speaking, mechanics is just a miscellany of experiential data and mathematical formulae." In terms still more general, one might say: "a miscellany of experiential data and logical inferences from such data." Suppose, for a moment, we call that non-science. Both Vera and Hegel are then right in saying that the theories of Newton are not science but non-science; and in these volumes I also intend to deal with non-science, since my wish is to construct a system of sociology on the model of celestial mechanics, physics, chemistry, and other similar non-sciences, and eschew entirely the science or sciences of the metaphysicists (§§ 503, 514).

21. A reader might observe: "That granted, why do you continually harp on science in the course of your book, since you use the term in the sense of non-science? Are you trying in that way to usurp for your non-science a prestige that belongs to science alone?" I answer that if the word "science" ordinarily meant what the metaphysicists say it means, rejecting the thing, I would conscientiously reject the word. But that is not the case. Many people, nay, most people, think of celestial mechanics, physics, chemistry, and so on as sciences; and to call them non-sciences or something else of the sort would, I fear, be ridiculous. All the same, if someone is still not satisfied, let him prefix a "non-" to the words "science" and "scientific" whenever he meets them in these volumes, and he will see that the exposition develops just as smoothly, since we are dealing with things and not with words (§ 119).

22. While metaphysics proceeds from absolute principles to concrete cases, experimental science proceeds from concrete cases, not to absolute principles, which, so far as it is concerned, do not exist, but to general principles, which are brought under principles still more general, and so on indefinitely. That procedure is not readily grasped by minds accustomed to metaphysical thinking, and it gives rise to not a few erroneous interpretations.

23. Let us note, just in passing, the preconception that in order to know a thing its "essence" must be known. To the precise contrary, experimental science starts with knowledge of things, to go on, if not to essences, which are entities unknown to science, at least to general principles (§§ 19-20). Another somewhat similar conception is widely prevalent nowadays in the fields of political economy and sociology. It holds that knowledge of things can be acquired only by tracing their "origins"1 (§§ 93, 346).

24. In an attenuated form the preconception requiring knowledge of "essences" aims at demonstrating particular facts by means of general principles, instead of deriving the general principle from the fact. Just so proof of the fact is confused with proof of its causes. For example, observation shows the existence of a fact A; and we go on and designate B, C, D . . . as its probable causes. It is later shown that those causes are not operative, and from that the conclusion is drawn that A does not exist. The demonstration would be valid if the existence of B, C, D . . . had been shown by experience and the existence of A inferred from them. It is devoid of the slightest value if observation has yielded A directly.

25. Close kin to the preconception just mentioned is the difficulty some people experience in analyzing a situation and studying its various aspects separately. We shall have frequent occasion to return to this matter. Suffice it here to note that the distinctions drawn above in § 13 will not be recognized by many people; and if others do indeed accept them theoretically, they straightway forget them in actual thinking (§§ 31-32, 817).

26. For people of "living faith" the various characteristics of theories designated in § 13 often come down to one only. What the believer wants to know, and nothing else, is whether the proposition is true or not true. Just what "true" means nobody knows, and the believer less than anybody. In a general way it seems to indicate accord with the believer's sentiments; but that fact is evident only to the person viewing the belief from the outside, as a stranger to it—never to the believer himself. He, as a rule, denies the subjective character of his belief. To tell him that it is subjective is almost to insult him, for he considers it true in an absolute sense. For the same reason he refuses to think of the term "true" apart from the meaning he attaches to it, and readily speaks of a truth different from experimental truth and superior to it.1

27. It is idle to continue discussions of that type—they can only prove fruitless and inconclusive—unless we know exactly what the terms that are used mean, and unless we have a criterion to refer to, a judge to render judgment in the dispute (§§ 17 f.). Is the criterion, the judge, to be experience and observation, or is it to be something else? That point has to be clearly determined before we can go on. If you are free to choose between two judges, you may pick the one you like best to decide your case. But you cannot choose them both at the same time, unless you are sure in advance that they are both of one mind and one will.

28. Of that agreement metaphysicists enjoy an a priori certitude, for their superexperimental criterion is of such majesty and power that it dominates the experimental criterion, which must of necessity accord with it. For a similar reason theologians too are certain a priori that the two criteria can never fail of accord. We, much more humble, enjoy no such a priori enlightenment. We have no knowledge whatever of what must or ought to be. We are looking strictly for what is. That is why we have to be satisfied with one judge at a time.

29. From our point of view not even logic supplies necessary inferences, except when such inferences are mere tautologies. Logic derives its efficacy from experience and from nothing else (§ 97).1

30. The human mind is synthetic, and only training in the habit of scientific thinking enables a few individuals to distinguish the parts in a whole by an analytical process (§ 25). Women especially, and the less well-educated among men, often experience an insurmountable difficulty in considering the different aspects of a thing separately, one by one. To be convinced of that one has only to read a newspaper article before a mixed social gathering and then try to discuss one at a time the various aspects under which it may be considered. One will notice that one's listeners do not follow, that they persist in considering all the aspects of the subject all together at one time.

31. The presence of that trait in the human mind makes it very difficult for both the person who is stating a proposition and the person who is listening to keep the two criteria, the experimental and the non-experimental, distinct. An irresistible force seems always to be driving the majority of human beings to confuse them. Many facts of great significance to sociology find their explanation in just that, as will be more clearly apparent from what follows.

32. In the natural sciences people have finally realized the necessity of analysis in studying the various aspects of a concrete phenomenon—the analysis being followed by a synthesis in getting back from theory to the concrete. In the social sciences that necessity is still not grasped by many people.

33. Hence the very common error of denying the truth of a theory because it fails to explain every aspect of a concrete fact; and the same error, under another form, of insisting on embracing under one theory all other similar or even irrelevant theories.

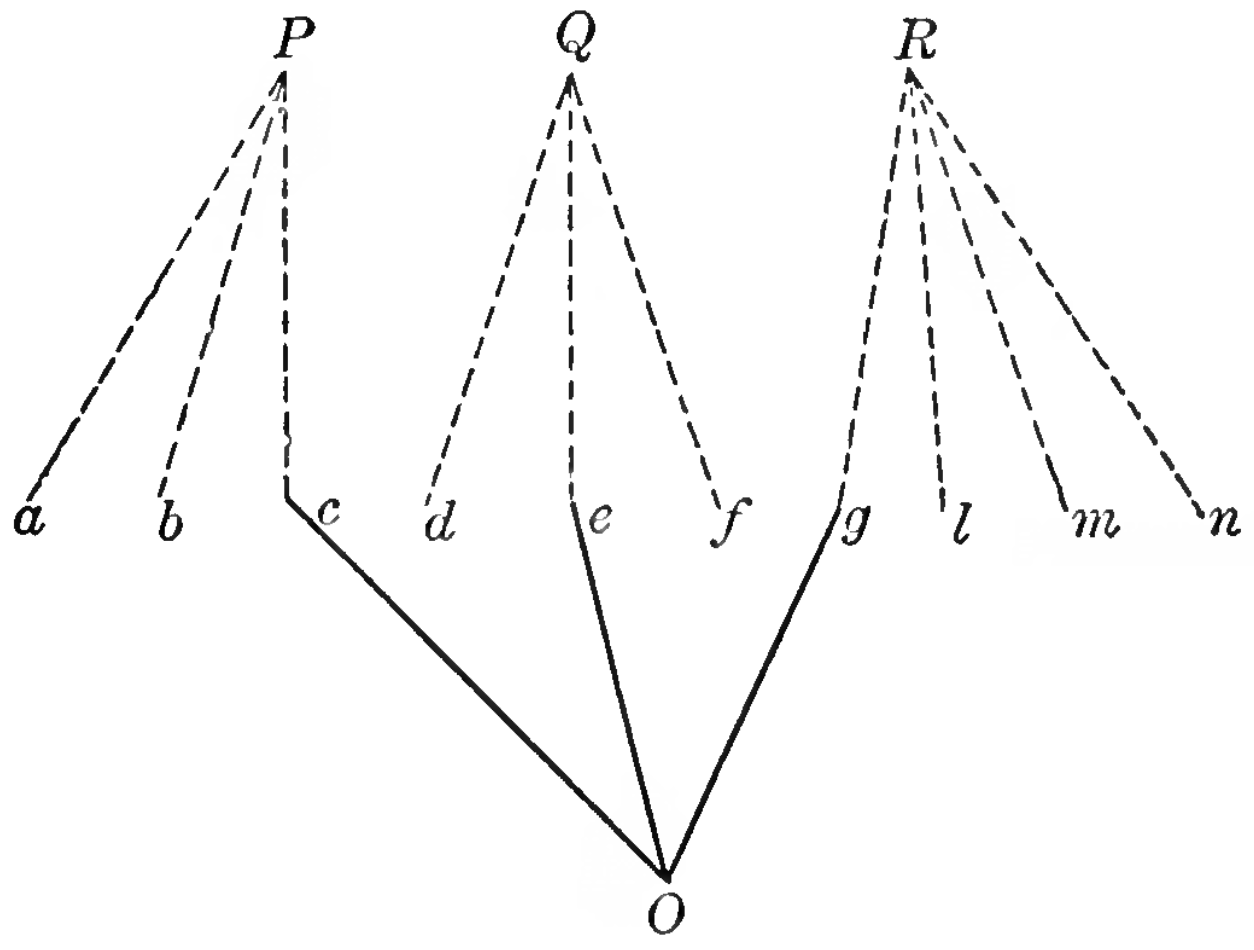

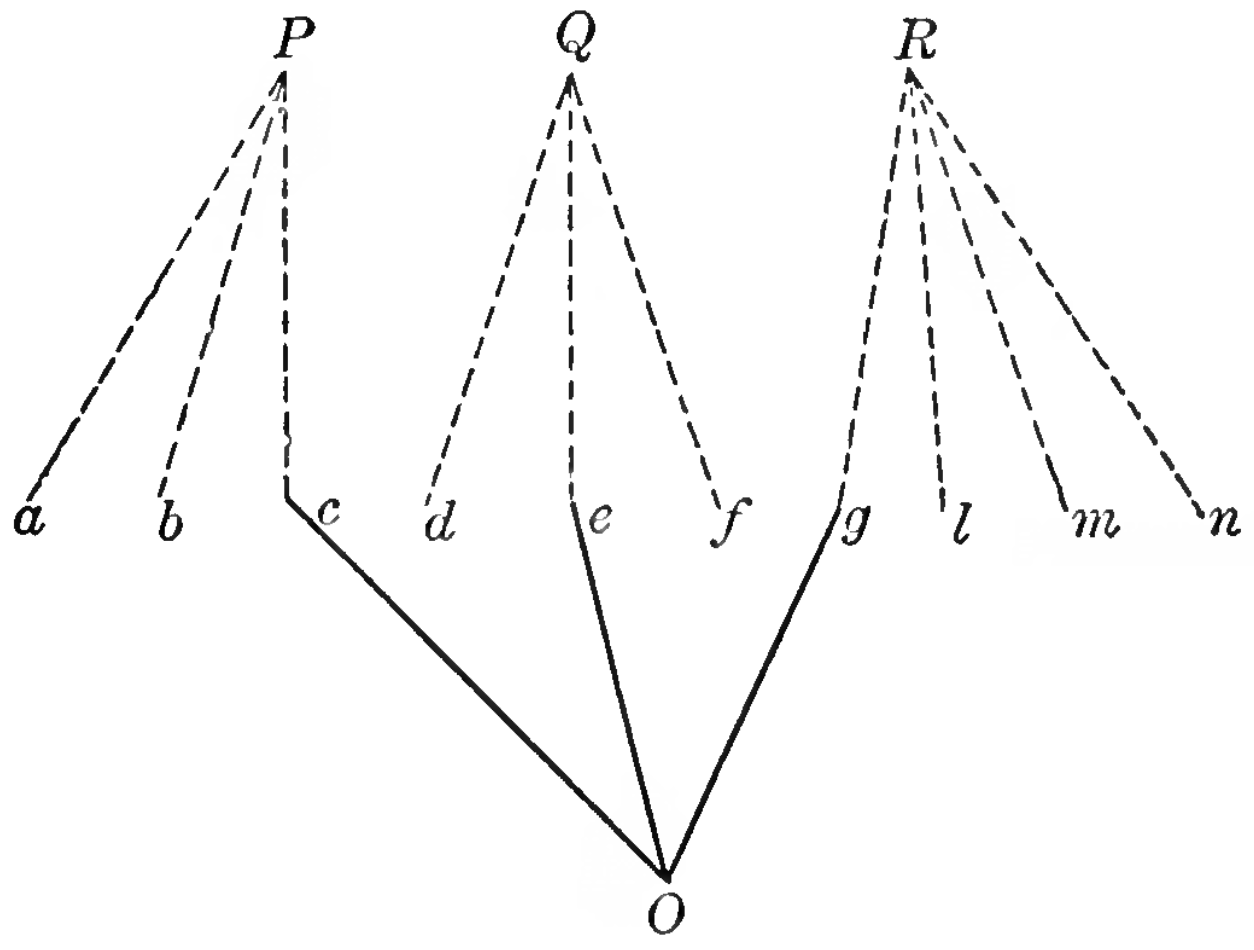

Let O in Figure 1 stand for a concrete situation. By analysis we distinguish within it a number of facts: c, e, g. . . .

The fact c and others like it, a, b . . . are brought together under a certain theory, under a general principle, P. In the same way, e and facts like e (d, f . . .) yield another theory, Q; and the facts g, i, m, n . . . still another theory, R, and so on. These theories are worked out separately; then, to determine the concrete situation O, the results (c, e, g . . .) of the various theories are taken together. After analysis comes synthesis.

People who fail to understand that will say: "The situation O presents not only the fact e but also the fact c; therefore the theory Q has to account for c." That conclusion is erroneous. One should say—and it is the only sound conclusion: ". . . therefore the theory Q accounts for only a part of the situation O."

34. Example: Let Q stand for the theory of political economy. A concrete situation O presents not only an economic aspect, e, but the further aspects c, g . . . of a sociological character. It is a mistake to include, as many have included, the sociological elements c, g . . . under political economy. The only sound conclusion to be drawn from the facts is that the economic theory which accounts for e must be supplemented (supplemented, not replaced) by other theories which account for c, g. . . .

35. In political economy itself, the theories of pure or mathematical economics have to be supplemented—not replaced—by the theories of applied economics. Mathematical economics aims chiefly at emphasizing the interdependence of economic phenomena. So far no other method has been found for attaining that end.1

36. Straightway one of those numberless unfortunates who are cursed with the mania for talking about things they do not understand comes forward with the discovery—lo the wonders of genius! —that pure economics is not applied economics, and concludes, not that something must be added to pure economics if we are to understand concrete phenomena, but that pure economics must be replaced by his gabble. Alas, good soul, mathematical economics helps, at least, to a rough understanding of the effects of the interdependence of economic phenomena, while your gabble shows absolutely nothing!

37. And lo, another prodigious genius, who holds that because many economic phenomena depend on the human will, economics must be replaced by psychology. But why stop at psychology? Why not geography, or even astronomy? For after all the economic factor is influenced by seas, continents, rivers, and above all by the Sun, fecundator general of "this fair family of flowers and trees and all earthly creatures."1 Such prattle has been called positive economics, and for that our best gratitude, for it provokes a laugh, and laughter, good digestion!

38. Many economists have been inclined to bring each and every sort of economic theory under the theory of value.1 True, nearly all economic phenomena express themselves in terms of value; but from that we have a right to conclude that in isolating the various elements in such phenomena we come upon a theory for value—but not that all other elements have to be squeezed into that theory. Nowadays people are going farther still, and value is coming to be the door through which sociology is made to elbow its way into political economy. Perhaps we ought to be thankful that they are stopping at that, for no end of other things might be pushed through the same door: psychology, to explain why and how a thing, real or imaginary, comes to have value; then physiology as handmaiden to psychology; and then—why not?—a little biology to explain the foundations of physiology; and surely a little mathematics, for after all the first member of an equation has the same value as the second and the theory of value would not be complete without the theory of equations; and so on forever. In all of which there is this much truth: that the concrete situation is very complex and may be regarded as a compound of many elements A, B, C. . . . Experience teaches that to understand such a situation it is best to isolate the elements A, B, C . . . and examine them one by one, that we may then bring them together again and so get the theory of the complex as a whole. That is just what logico-experimental science does. But those who are unfamiliar with its methods grope blindly forward, shifting from A to B, from B to C, then every so often turning back, mixing things up, taking refuge in words, thinking of B while studying A, and of something else while studying B. Worse yet, if you are looking into A they interrupt to remind you of B; and if you answer on B, they are off to C, jumping about now here, now there, prattling ever beside the point and demonstrating one thing only: their helpless innocence of any scientific method.

39. Those who deny scientific status to political economy argue, in fact, to show that it is not adequate to explain concrete phenomena; and from that they conclude that it should be ignored in such explanation. The sound conclusion would be that other theories should be added to it. Thinking as such people think we should have to say that chemistry ought to be ignored in agriculture, since chemistry is inadequate to explain everything about a farm. Moreover, engineering schools would have to bar pure mathematics, for it stands to applied mechanics almost as pure economics stands to applied economics.

40. Further, it is difficult, in fact almost impossible, to induce people to keep mere knowledge of the laws (uniformities) of society distinct from action designed to modify them. If someone is keeping strictly to such knowledge, people will insist at all costs that he have some practical purpose in view. They try to find out what it is, and, there being none, one is finally invented for him.

41. In the same way, it is difficult to induce people not to go beyond what an author says and add to the propositions he states others that may seem to be implicit in them but which he never had in mind (§§ 73 f., 311). If you note a defect in a given thing A, it is taken for granted that you are condemning A as a whole; if you note a good point, that you approve of A as a whole. It seems incredibly strange to people that you should be stressing its defects if you are not intending to condemn it as a whole, or its excellences if you are not approving of it as a whole. The inference would be somewhat justified in a case of special pleading, for after all it is not the business of the advocate to accuse his client. But it is not a sound inference from a plain description of fact, or when a scientist is seeking scientific uniformities. The inference would be admissible, further, in the case of an argument not of a logico-experimental character but based on accord of sentiments (§ 514). In fact, when one is trying to win the sympathies of others by such an argument, one may be expected to declare one's own sympathies; and if that is not done explicitly, people may properly assume that it is done implicitly. But when we are reasoning objectively, according to the logico-experimental method, we are not called upon to declare our sentiments either explicitly or by implication.

42. As regards proofs, a person stating a logico-experimental proposition or theory (§ 13, Ia) asks them of observation, experience, and logical inferences from observation and experience. But the person asserting a proposition or theory that is not logico-experimental can rely only on the spontaneous assent of other minds and on the more or less logical inferences he can draw from what is assented to. At bottom he is exhorting rather than proving. However, that is not commonly admitted by people using non-logico-experimental theories. They pretend to be offering proofs of the same nature as the proofs offered for logico-experimental theories; and in such pseudo-experimental arguments they take full advantage of the indefiniteness of common everyday language.

As regards persuasion, proofs are convincing only to minds trained to logico-experimental thinking. Authority plays a great part even in logico-experimental propositions, though it has no status as proof. Passions, accords of sentiment, vagueness of terms, are of great efficacy in everything that is not logico-experimental (§ 514).

43. In the sphere of proof, experience is powerless as against faith, and faith as against experience, with the result that each is confined to its own domain. If John, an unbeliever, denies that God created Heaven and Earth, and you meet him with the authority of the Bible, you have made a nice round hole in the water, for he will deny the authority of the Bible and your argument will crumble. To replace the authority of the Bible with the authority of your "Christian experience" is a childish makeshift, for John will reply that his own experience inclines him not in the least to agree with you; and if you retort that his experience is not Christian, you will have reasoned in a neat circle, for it is certain that if only that experience is Christian which leads to your results, one may conclude without fear of contradiction that Christian experience leads to your results—and by that we have learned exactly nothing.

44. When one asserts a logico-experimental proposition (§ 13, Ia), one can place those who contradict in the dilemma of either accepting the proposition as true or refusing credence to experience and logic. Anyone adopting the latter course would be in the position of John, the unbeliever just mentioned: you would have no way of persuading him.

45. It is therefore evident that, aside as usual from sophistical reasonings made in bad faith, the difference as regards proofs between theories that are logico-experimental (Ia) and theories that are not lies chiefly in the fact that in our day in Western countries it is easier to find disbelievers in the Koran or the Gospels; in types of experience, whether Christian, personal, humanitarian, rational, or of whatever other kind; in the categorical imperative; or in the dogmas of positivism, nationalism, pacifism, and numberless other things of that brand, than it is to find disbelievers in logic and experience. In dealing with other ages and countries the situation maybe different.

46. We are in no sense intending, in company with a certain materialistic metaphysics, to exalt logic and experience to a greater power and majesty than dogmas accepted by sentiment. Our aim is to distinguish, not to compare, and much less to pass judgment on the relative merits and virtues of those two sorts of thinking (§ 69).

47. Again, we have not the remotest intention of bringing back through the window a conviction we have just driven out by the door. We in no wise assert that the logico-experimental proof is superior to the other and is to be preferred. We are saying simply—and it is something quite different—that such proof alone is to be used by a person concerned not to abandon the logico-experimental field.1

48. The extreme case of a person flatly repudiating all logical discursion, all experience, is rarely met with. Logico-experimental considerations are commonly enough ignored, left unexpressed, crowded aside, by one device or another; but it is difficult to find anyone really combating them as enemies. That is why people almost always try to demonstrate theories that are not objective, not experimental, by pseudo-logical and pseudo-experimental proofs.

49. All religions have proofs of that type, supplemented as a rule by proofs of utility to individual and society. And when one religion replaces another, it is anxious to create the impression that its experimental proofs are of a better quality than any the declining faith can marshal. Christian miracles were held to be more convincing than pagan miracles, and nowadays the "scientific" proofs of "solidarity" and humanitarianism are considered superior to the Christian miracles. All the same, the man who examines such facts without the assistance of faith fails to notice any great difference in them: for him they have exactly the same scientific value, to wit, zero. We are obliged to believe that "when Punic fury thundered from the Thrasimene" the defeat of the Romans was caused by the impious indifference of the consul Flaminius to the portents sent of the gods. The consul had fallen from his horse in front of the statue of Jupiter Stator. The sacred chickens had refused to eat. Finally, the legionary ensign had stuck in the ground and could not be extricated.1 We shall also be certain (whether more or less certain, I could not say) that the victory of the Crusaders at Antioch was due to the divine protection concretely symbolized in the Holy Lance.2 Then again it is certain, in fact the height of certitude, because attested by a better and more modern religion, that Louis XVI of France lost his throne and his life simply because he did not love to the degree required his good, his darling, people. The humanitarian god of democracy never suffers such offences to go unpunished!

50. Experimental science has no dogmas, not even the dogma that experimental facts can be explained only by experience. If the contrary were seen to be the case, experimental science would accept the fact, as it accepts every other fact of observation. And it in truth accepts the proposition that inventions may at times be promoted by non-experimental principles, and does so because that proposition is in accord with the results of experience.1 But so far as demonstration goes, the history of human knowledge clearly shows that all attempts to explain natural phenomena by means of propositions derived from religious or metaphysical principles have failed. Such attempts have finally been abandoned in astronomy, geology, physiology, and all other similar sciences. If traces of them are still to be found in sociology and its subbranches, law, political economy, ethics, and so on, that is simply because in those fields a strictly scientific status has not yet been attained.2

51. One of the last efforts to subordinate experience to metaphysics was made by Hegel in his Philosophy of Nature, a work which, in all frankness, attains and oversteps the limits of comic absurdity.1

52. On the other hand, in our day people are beginning to repudiate dogmas that usurp status as experimental science. Sectarians of the humanitarian cult are wont to meet the "fictions" of the religion they are combating with the "certainty" of science. But that "certainty" is just one of their preconceptions. Scientific theories are mere hypotheses, which endure so long as they accord with the facts and which die and vanish from the scene as new investigations destroy that accord. They are then superseded by new ones for which a similar fate is held in store (§ 22).

53. Let us assume that a certain number of facts are given. The problem of discovering their theory may be solved in more than one way. A number of theories may satisfy the data equally well, and the choice between them may sometimes be determined by subjective considerations, such as preference for greater simplicity (§ 64).

54. In both logico-experimental (Ia) and non-logico-experimental theories, one gets certain general propositions called "principles," logically deducible from which are inferences constituting theories. Such principles differ entirely in character in the two kinds of theories mentioned.

55. In logico-experimental theories (Ia) principles are nothing but abstract propositions summarizing the traits common to many different facts. The principles depend on the facts, not the facts on the principles. They are governed by the facts, not the facts by them. They are accepted hypothetically only so long and so far as they are in agreement with the facts; and they are rejected as soon as there is disagreement (§ 63).

56. But scattered through non-logico-experimental theories one finds principles that are accepted a priori, independently of experience, dictating to experience. They do not depend upon the facts; the facts depend upon them. They govern the facts; they are not governed by them. They are accepted without regard to the facts, which must of necessity accord with the inferences deducible from the principles; and if they seem to disagree, one argument after another is tried until one is found that successfully re-establishes the accord, which can never under any circumstances fail.

57. In order of time, the grouping of theories as given in § 13 has in many cases to be reversed. In history, that is, non-logico-experimental theories often come first, the logico-experimental (Ia) afterwards.

58. The subordination of facts to principles in non-logico-experimental theories is manifested in a number of ways:

1. People are so sure of the principles with which they start that they do not even take the trouble to inquire whether their implications are in accord with experience. Accord there must be, and experience as the subordinate cannot, must not, be allowed to talk back to its superior.1 That is the case especially when logico-experimental theories (Ia) begin to invade a domain that has been pre-empted by non-logico-experimental theories.

2. As that invasion gains headway, progress in the experimental sciences finally rescues them from the servitude to which they were regarded as sternly subject. They are conceded a measure of autonomy; they are permitted to verify the inferences drawn from traditional principles, though people continue to assert that verification always corroborates the principle. If things seem not to turn out that way, casuistry comes to the rescue to re-establish the desired accord.

3. When finally that method of maintaining the sovereignty of the general principles also fails, the experimental sciences are resignedly allowed to enjoy their hard-won independence; but their domain is now represented as of an inferior order envisaging the relative and the particular, whereas philosophical principles contemplate the absolute, the universal.

59. No departure from the experimental field and therefore from the domain of logico-experimental theories (Ia) is involved in the resort to hypotheses, provided they are used strictly as instruments in the quest for consequences that are uniformly subject to verification by experience. The departure arises when hypotheses are used as instruments of proof without reference to experimental verification. The hypothesis of gravitation, for instance, does not carry us outside the experimental field so long as we understand that its implications are at all times subject to experience, as modern physics always assumes. It would carry us outside the experimental field were we to declare gravitation an "essential property" of "matter" and assert that the orbits of the stars must of necessity comply with the Newtonian law. That distinction was not grasped by writers such as Comte, who tried to bar the hypothesis of a luminous ether from science. That hypothesis and others of the kind are to be judged not intrinsically but extrinsicallv, that is, by ascertaining whether and to what extent inferences drawn from them accord with the facts.

60. When any considerable number of inferences from a given hypothesis have been verified by experience, it becomes exceedingly probable that a new implication will likewise be verified; so in that case the two types of hypotheses mentioned in §§ 55 and 56 are inclined to blend, and in practice there is the temptation to accept the new inference without verifying it. That explains the haziness present in many minds as to the distinction between hypotheses subordinate to experience and hypotheses dominating experience. Still, as a matter of practice there are cases where the implications of this or that hypothesis may be accepted without proof. For instance, certain principles of pure mechanics are being questioned nowadays, at least as regards velocities to any considerable degree greater than velocities practically observable. But it is evident that the mechanical engineer may continue to accept them without the slightest fear of going wrong, since the parts of his machines move at speeds which fall far short of any that would require modifications in the principles of dynamics.

61. In pure economics my hypothesis of "ophelimity" (§ 2110) remains experimental so long as inferences from it are held subject to verification on the facts. Were that subordination to cease, the hypothesis could no longer be called experimental. Walras did not think of his "exchange value" in any such manner.1 If one drops the hypothesis of ophelimity, as is possible by observing curves of indifference (§ 24081) or by some other device of the kind, one is excused from verifying experimentally the implications of a hypothesis that is no longer there.

62. Likewise, the hypothesis of value remains experimental so long as value is thought of as something leading to inferences that are experimentally verifiable. It ceases to be experimental when value is taken as a metaphysical entity presumably superior to experimental verification (§ 104).1

63. In the logico-experimental sciences, if they are to be kept strictly such, so-called general principles are, as we said above (§ 55), nothing but hypotheses designed to formulate syntheses of facts linking facts under theories and epitomizing them. Theories, their principles, their implications, are altogether subordinate to facts and possess no other criterion of truth than their capacity for picturing them. That is an exact reversal of the relations between general principles and experimental facts that obtain in non-logico-experimental theories (§ 13, Class II). But the human mind has such a predilection for theories of that sort that general principles have often been seen to recover sovereignty even over theories aspiring to status as logico-experimental (Ia). It was agreed, that is, that principles had a quasi-independent subsistence, that only one theory was true, while numberless others were false, that experience could indeed determine which theory was true, but that, having done that much, it was called upon to submit to the theory. In a word, general principles, which were lords by divine right in non-logico-experimental theories (§ 16), became lords by election, but lords nevertheless, in logico-experimental theories (Ia). So we get the two subclasses distinguished in § 13; but it is well to note that oftentimes their traits are implicit rather than explicit, that is, general principles are used without explicit declaration as to just how they are regarded.

64. Steady progress in the experimental sciences eventually brought about the downfall of this elective sovereignty as well, and so led to strictly logico-experimental theories (Ia1), in which general principles are mere abstractions devised to picture facts, it being meantime recognized that different theories may be equally true (§ 53), in the sense that they picture the facts equally well and that choice among them is, within certain limits, arbitrary. In a word, one might say that we have reached the extreme of Nominalism, provided that term be stripped of its metaphysical connotations.

65. For the very reason that we intend to remain strictly within logico-experimental bounds, we are not called upon to solve the metaphysical problem of Nominalism and Realism.1 We do not presume to decide whether only the individuum, or only the species, exists, for the good reason, among others, that we are not sufficiently clear as to the precise meaning of the term "exist." We intend to study things and hence individua, and to consider species as aggregates of more or less similar things on which we determine ourselves for specified purposes. Farther than that we choose not to go just here, though without prejudice to anybody's privilege of going beyond the point at which we stop.

66. The fact that we deal with individua by no means implies that a number of indiuidua taken together are to be considered a simple sum. They form compounds which, like chemical compounds, may have properties that are not the sum of the properties of their components.

67. Whether the principle that replaces experience or observation be theological, metaphysical, or pseudo-experimental may be of great importance from certain points of view; but it is of no importance whatever from the standpoint of the logico-experimental sciences. St. Augustine denies the existence of antipodes because Scripture makes no mention of them.1 In general, the Church Fathers find all their criteria of truths, even of experimental truths, in Holy Writ. Metaphysicists make fun of them and replace their theological principles with other principles just as remote from experience. Scientists who came after Newton, forgetting that he had wisely halted at the dictum that celestial bodies moved as if by mutual attraction according to a certain law, saw in that law an absolute principle, divined by human intelligence, verified by experience, and presumably governing all creation eternally. But the principles of mechanics have of late been subjected to searching criticism, and the conclusion has been reached that only facts and the equations that picture them can stand. Poincaré judiciously observes that from the very fact that certain phenomena admit of a mechanical explanation, they admit also of an indefinite number of other explanations.

68. All the natural sciences to a greater or lesser extent are approximating the logico-experimental type (Ia1). We intend to study sociology in just that fashion, trying, that is, to reduce it to the same type (§§ 6, 486, 5142).

69. The course we elect to pursue in these volumes is therefore the following:

1. We intend in no way to deal with the intrinsic "truth" of any religion or faith, or of any belief, whether ethical, metaphysical, or otherwise, and we adopt that resolve not in any scorn for such beliefs, but just because they lie beyond the limits within which we have chosen to confine ourselves. Religions, beliefs, and the like we consider strictly from the outside as social facts, and altogether apart from their intrinsic merits. The proposition that "A must1 be equal to B" in virture of some higher superexperimental principle escapes our examination entirely (§ 46); but we do want to know how that belief arose and developed and in what relationships it stands to other social facts.

2. The field in which we move is therefore the field of experience and observation strictly. We use those terms in the meanings they have in the natural sciences such as astronomy, chemistry, physiology, and so on, and not to mean those other things which it is the fashion to designate by the terms "inner" or "Christian" experience, and which revive, under barely altered names, the "introspection" of the older metaphysicists. Such introspection we consider as a strictly objective fact, as a social fact, and not as otherwise concerning us.

3. Not intruding on the province of others, we cannot grant that others are to intrude on ours.2 We deem it inept and idiotic to set up experience against principles transcending experience: but we likewise deny any sovereignty of such principles over experience.3

4. We start with facts to work out theories, and we try at all times to stray from the facts as little as possible. We do not know what the "essences" of things are (§§ 19, 91, 530) and we ignore them, since that investigation oversteps our field (§ 91). We are looking for the uniformities presented by facts,4 and those uniformities we may even call laws (§ 99); but the facts are not subject to the laws: the laws are subject to the facts. Laws imply no necessity (§§ 29, 97). They are hypotheses serving to epitomize a more or less extensive number of facts and so serving only until superseded by better ones.

5. Every inquiry of ours, therefore, is contingent, relative, yielding results that are just more or less probable, and at best very highly probable. The space we live in seems actually to be three-dimensional; but if someone says that the Sun and its planets are one day to sweep us into a space of four dimensions, we shall neither agree nor disagree. When experimental proofs of that assertion are brought to us, we shall examine them, but until they are, the problem does not interest us. Every proposition that we state, not excluding propositions in pure logic, must be understood as qualified by the restriction within the limits of the time and experience known to us (§ 97).

6. We argue strictly on things and not on the sentiments that the names of things awaken in us. Those sentiments we study as objective facts strictly. So, for example, we refuse to consider whether an action be "just" or "unjust," "moral" or "immoral," unless the things, to which such terms refer have been clearly specified. Wey shall, however, examine as an objective fact what people of a given social class, in a given country, at a given time, meant when they said that A was a "just" or a "moral" act. We shall see what their motives were, and how oftentimes the more important motives have done their work unbeknown to the very people who were inspired by them; and we shall try to determine the relationships between such facts and other social facts. We shall avoid arguments involving terms lacking in exactness (§ 486), because from inexact premises only inexact conclusions can be drawn.5 But such arguments we shall examine as social facts; indeed, we have in mind to solve a very curious problem as to how premises altogether foreign to reality sometimes yield inferences that come fairly close to reality (Chapter XI).

7. Proofs of our propositions we seek strictly in experience and observation, along with the logical inferences they admit of, barring all proof by accord of sentiments, "inner persuasion," "dictate of conscience."

8. For that reason in particular we shall keep strictly to terms corresponding to things, using the utmost care and endeavour to have them as definite as possible in meaning (§ 108).

9. We shall proceed by successive approximations. That is to say, we shall first consider things as wholes, deliberately ignoring details. Of the latter we shall then take account in successive approximations (§ 540).6

70. We in no sense mean to imply that the course we follow is better than others, for the reason, if for no other, than the term "better" in this case has no meaning. No comparison is possible between theories altogether contingent and theories recognizing an absolute. They are heterogeneous things and can never be brought together (§ 16). If someone chooses to construct a system of sociology starting with this or that theological or metaphysical principle or, following a contemporary fashion, with the principles of "progressive democracy," we shall pick no quarrel with him, and his work we shall certainly not disparage. The quarrel will not become inevitable until we are asked in the name of those principles to accept some conclusion that falls within the domain of experience and observation. To go back to the case of St. Augustine: When he asserts that the Scriptures are inspired of God, we have no objection to the proposition, which we do not comprehend very clearly to begin with. But when he sets out to prove by the Scriptures that there are no antipodes (§ 485), we have no interest in his arguments, since jurisdiction in the premises belongs to experience and observation.1

71. We move in a narrow field, the field, namely, of experience and observation. We do not deny that there are other fields, but in these volumes we elect not to enter them. Our purpose is to discover theories that picture facts of experience and observation (§ 486), and in these volumes we refuse to go beyond that. If anyone is minded to do so, if anyone craves an excursion outside the logico-experimental field, he should seek other company and drop ours, for he will find us disappointing.

72. We differ radically from many people following courses similar to ours in that we do not deny the social utility of theories unlike our own. On the contrary we believe that in certain cases they may be very beneficial. Correlation of the social utility of a theory with its experimental truth is, in fact, one of those a priori principles which we reject (§ 14). Do the two things always go hand in hand, or do they not? Observation of facts alone can answer the question; and the pages which follow will furnish proofs that the two things can, in certain cases, be altogether unrelated.

73. I ask the reader to bear in mind, accordingly, that when I call a doctrine absurd, in no sense whatever do I mean to imply that it is detrimental to society: on the contrary, it may be very beneficial. Conversely, when I assert that a theory is beneficial to society, in no wise do I mean to imply that it is experimentally true. In short, a doctrine may be ridiculed on its experimental side and at the same time respected from the standpoint of its social utility. And vice versa.

74. In general, when I call attention to some untoward consequence of a thing A, indeed one very seriously so, in no way do I mean to imply that A on the whole is detrimental to society; for there may be good effects to overbalance the bad. Conversely, when I call attention to a good effect of A, great though it be, I do not at all imply that on the whole A is beneficial to society.

75. The warning I have just given I had to give, for in general people writing on sociology for purposes of propaganda and with ideals to defend speak in unfavourable terms alone of things they consider bad on the whole, and favourably of things they consider good on the whole. Furthermore, since to a greater or lesser extent they use arguments based on accords of sentiment (§§ 41, 514), they are induced to manifest their own sympathies in order to win the sympathies of others. They look at facts with not altogether indifferent eyes. fThey love and they hate, and they disclose their loves and their hates, their likes and dislikes. Accustomed to that manner of doing and saying, a reader very properly concludes that if a writer speaks unfavourably of a thing and stresses one or another of its defects, that means that on the whole he judges it bad and is unfavourably disposed towards it; whereas if he speaks favourably of a thing and stresses one or another of its good points, on the whole he deems it good and is favourably disposed towards it. That rule does not apply to this work; and I shall feel obliged to remind the reader of that fact over and over again (§ 311). In these volumes I am reasoning objectively, analytically, according to the logico-experimental method. In no way am I called upon to make known such sentiments as I may happen to cherish, and the objective judgment I pass upon one aspect of a thing in no sense implies a similar judgment on the thing considered synthetically as a whole.1

76. If one person would persuade another on matters pertaining to experimental science, he chiefly and, better yet, exclusively, states facts and logical implications of facts (§ 42). But if he would persuade another on matters pertaining to what is still called social science, his chief appeal is to sentiments, with a supplement of facts and logical inferences from facts. And he must proceed in that fashion if his idea is to talk not in vain; for if he were to disregard sentiments, he would persuade very few and in all probability fail to get a hearing at all, whereas if he knows how to play deftly on sentiments, his reputation for eloquence will soar (§ 514).1

77. Political economy has hitherto been a practical discipline designed to influence human conduct in one direction or another. It could hardly be expected, therefore, to avoid addressing sentiment, and in fact it has not done so. All along economists have given us systems of ethics supplemented in varying degree with narrations of facts and elaborations of the logical implications of facts. That is strikingly apparent in the writings of Bastiat; but it is apparent enough in virtually all writings on economics, not excluding works of the historical school, which are oftentimes more metaphysical and sentimental than the rest. As mere examples of forecasts based on the scientific laws of political economy and sociology (to the exclusion of sentiment), I offer the following. The first volume of my Cours appeared in the year 1896, but had been written in 1895, with statistical tables coming down not later than the year 1894.

1. Contrarily to the views of ethical sociologists, whether of the historical school or otherwise, and of sentimental anti-Malthusians, at that time I wrote with reference to population increase: "We are therefore witnessing rates of increase in our day that cannot have obtained in times past and cannot continue to hold in the future."1 And I mentioned in that connexion the examples of England and Germany. As for England, there were already signs of a slackening. Not so for Germany, where there were as yet no grounds, empirically, for arriving at any conclusions whatever. But now both countries show a declining curve.2

2. With specific reference to England, after determining the law of population increase for the years 1801-91, I concluded that popu lation could not continue to increase at the same rate. And the rate has in fact fallen.3

3. "The gains made by certain Socialistic ideas in England are probably the result of an increment in the economic obstacles to population increase."4 The soundness of that conclusion is even more apparent now. Socialism has progressed in England, while a falling-off has been observable in the other countries in Europe.

4. In Chapter XII we shall see a verification of a sociological law that I used in my Systèmes socialistes.

5. The second volume of my Cours was published in 1897. At that time it was an article of faith with many people that social evolution was in the direction of the rich growing richer and the poor, poorer. Contrarily to that sentimental view, the law of distribution of income led to the proposition5 that "if total income increases with respect to population, there must be either an increase in the minimum income, or a decrease in inequality in incomes, or the two things must result simultaneously." Between 1897 and 1911 there was an increase in total income as compared with population, and what in fact resulted was an increase in minimum income and a decrease in inequality in incomes.6 A counter-proof, furthermore, is available in the fact that my Cours is defective in those sections into which sentiment was allowed to intrude.7

78. A person often accepts a proposition for no other reason than that it accords with his sentiments. Such accord, indeed, usually makes a proposition more "obvious." And from the standpoint of social utility in many cases it is perhaps well that that be so. But from the standpoint of experimental science, such accord has little value and often none whatever. Of that I shall give many examples.

79. Since I intend in these volumes to take my stand strictly within the field of experimental science, I shall try to avoid any appeal to the reader's sentiments whatsoever and keep to facts and implications of facts.1

80. When a writer is "doing literature" or addressing sentiments in any way at all, he finds it necessary, in deference to them, to choose between the facts he uses. Not all of them rise to the dignity of rhetorical or historical propriety. There is an aristocracy of facts reference to which is always commendable. There is a commonalty of facts reference to which incurs neither praise nor blame. There is a proletariat of facts reference to which is at all times improper and reprehensible. So amateur entomologists may find it pleasant to catch bright-coloured butterflies, just routine to catch flies and wasps, loathsome to lay hand to dung- and carrion-beetles. But the naturalist knows no such distinctions, nor do they arise for us in the field of social science (§§ 85, 896).

81. We keep open house to all facts, whatever their character, provided that directly or indirectly they point the way to discovering a uniformity. Even an absurd, an idiotic argument is a fact, and if accepted by any large number of people, a fact of great importance to sociology. Beliefs, whatever their character, are also facts, and their importance depends not on their intrinsic merits, but on the greater or fewer numbers of individuals who profess them. They serve furthermore to reveal the sentiments of such individuals, and sentiments are among the most important elements with which sociology is called upon to deal (§ 69-6).

82. The reader must bear that in mind, as he encounters in these volumes facts which at first blush might seem insignificant or childish. Tales, legends, the fancies of magic or theology, may often be accounted idle and ridiculous things—and such they are, intrinsically; but then again they may be very helpful as tools for discovering the thoughts and feelings of men. So the psychiatrist studies the ravings of the lunatic not for their intrinsic worth but for their value as symptoms of disease.

83. The road that is to lead us to the uniformities we seek may at times seem a long one. If that is the case, it is simply because I have not succeeded in finding a shorter. If someone manages to do so, all the better; I will straightway leave my road for his. Meantime I deem it the wiser part to push on along the only trail as yet blazed.

84. If one's aim is to inspire or re-enforce certain sentiments in men, one must present facts favourable to that design and keep unfavourable data quiet. But if one is interested strictly in uniformities, one must not ignore any fact that may in any way serve to disclose them. And since my aim in these volumes is no other, I refuse out of hand to consider in a fact anything but its logico-experimental significance.

85. The one concession that I can make—and really it is not so much a concession as a grasp at some method for securing a far greater clearness by removing from the reader's eyes any veil that sentiment may have drawn across them—is to choose from the multitude of facts such as, in my judgment, will exert least influence upon sentiments. So when I have facts of equal experimental value before me from the past and from the present, I choose facts of the past. That accounts for my many quotations from Greek and Latin writers. In the same way, when I have facts of equal experimental value from religions now extinct and religions still extant, I give my preference to the former. But to prefer a thing is not to use it exclusively. In many many cases I am constrained to use facts from the present or from religions still existing, sometimes because I have no other facts of an equivalent experimental value, sometimes in order to show the continuity of certain phenomena from past to present. In such connexions I intend to write with absolute freedom; and the same frankness I maintain against the malevolence of our modern Paladins of Purity, for whom I care not the proverbial fig.1

86. In propounding this or that theory an author as a rule wants other people to assent to it and adopt it—in him the seeker after experimental truth and the apostle stand combined. In these volumes I keep those attitudes strictly separate, retaining the first and barring the second. I have said, and I repeat, that my sole interest is the quest for social uniformities, social laws. I am here reporting on the results of my quest, since I hold that in view of the restricted number of readers such a study can have and in view of the scientific training that may be taken for granted in them, such a report can do no harm. I should refrain from doing so if I could reasonably imagine that these volumes were to be at all generally read (§§ 14, 1403).1

87. Long ago in my Manuale, Chap. I, § 1, I wrote: "It is possible for an author to aim exclusively at hunting out and running down uniformities among facts—their laws, in other words—without having any purpose of direct practical utility in mind, any intention of offering remedies and precepts, any ambition, even, to promote the happiness and welfare of mankind in general or of any part of mankind. His purpose in such a case is strictly scientific: he wants to learn, to know, and nothing more. I warn the reader that in this Manual I am trying exclusively to realize this last purpose only. Not that I underrate the others. I am just drawing distinctions between methods, separating them and indicating the one that is to be followed in this book. Anyone differently minded can find plenty of books to his liking. He should feast on them and leave this one alone, for, as Boccaccio said of his tales [Decameron, X, Conclusione], it does not go begging a hearing of anybody."

Such a declaration seems to me clear enpugh, and I confess that I could not express myself in plainer terms. Yet I have been credited with intentions of reforming the world, and even been compared to Fourier!1